Abstract

This paper tracks the jurisprudential development of Article 184 (3) of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, across 941 cases from 1973 to 2019. The purpose of this consolidated research paper is to trace the origins of the suo motu power, while highlighting its obvious textual absence. For this purpose, this paper synthesises data on the Supreme Court’s reading of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3) during three time periods: The pre-Darshan Masih, the Darshan Masih, and the post-Darshan Masih eras. The study highlights the Supreme Court’s varied reading of Public Interest Litigation as a legal tool and inconsistent deployment of statutory interpretational techniques. Finally, this paper analyses the implications that an expansive interpretation and complete subversion of Article 184 (3)’s procedural requirements has had on the dissemination of fundamental rights, doctrine of separation of powers, and the Court’s questionable role as a framer of public policy.

Keywords: suo motu, public interest litigation, public importance, fundamental rights, judicial restraint, separation of powers.

Introduction

Justice Fazal Karim, a former judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, and a distinguished constitutional law scholar, refers to suo motu, the power of the Supreme Court to hear cases on its own accord, to be one that is “self-created” in the Pakistani constitutional context. While recommending changes to the constitutional framework of the country, the retired judge argues that the Supreme Court has extra-constitutionally assumed the power of suo motu and it has been vastly expanded by certain judicial celebrities. Before recommending a constitutional amendment to disarm the Court of this power, Justice Fazal Karim highlights his disapproval for the judicial practice of suo motu by labelling it “wholly inconsistent with the constitutional concept of Judicial Power.” However, it is essential to note that the Justice’s critique of suo motu powers is embedded primarily in its facilitation of judicial over-reach, subversion of procedure, and violation of the constitutional doctrines such as that of separation of powers – all concepts that this paper will elaborate upon. However, it is imperative at this stage to take a step backward from his perspective and scrutinise the constitutional text from which the Pakistani judiciary purports to derive this invasive power.

Article 184 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan confers original jurisdiction, the authority to hear a case at its initiation, often referred to as Public Interest Litigation, in the form of judicial review to Pakistan’s Supreme Court. Clause (3) of Article 184, however, is cited as the source of suo motu powers by those who employ it. The text of this constitutional provision is as follows:

Without prejudice to the provisions of Article 199, the Supreme Court shall, if it considers that a question of public importance with reference to the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights conferred by Chapter 1 of Part II is involved, have the power to make an order of the nature mentioned in the said Article.

A perusal of the provision, as mentioned above, highlights three main features. Firstly, it contains a “without prejudice” clause. This, according to Chief Justice Muhammad Haleem, in the Wukala Mahaz case, preserves the High Courts’ power to conduct judicial review and allows affected petitioners to choose between either the Supreme Court or the High Courts for remedy. The next two features of this constitutional provision pertain to two procedural requirements that need to be met if a claim raised under this provision is to succeed. The text of Article 184 (3) stipulates that for the Court to have original jurisdiction on an issue, it first needs to be of public importance. Secondly, that issue must involve a violation of fundamental rights that are enshrined within the first chapter of the second part of the Pakistani Constitution. A perusal of the text of the constitutional provision makes it abundantly clear that the two conditions must be met for a petition of Public Interest Litigation to be maintainable. More importantly, the text of 184 (3) does not hint at even the slightest exemption of Public Interest Litigation cases from the conventional rules of procedure, such as those of locus standi, and the Supreme Court being the forum of last resort, to name a few.

The application of Article 184 (3) is where the text becomes irrelevant, and statutory interpretation dominates. The most recent interpretation of Article 184 (3) depicts a clear divergence from the text. Currently, the provision, as mentioned above, is interpreted by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, such that it allows the Court to exercise suo motu powers despite its textual nonexistence, in the provision or anywhere else in the Constitution. The Supreme Court has unilaterally chosen to read a judicial phenomenon which has no vestige in the Constitution and thereby empowered itself with the means to exert judicial will under the garb of enforcing fundamental rights. It is, however, essential to note that the Constitution does mention suo motu powers, but only concerning the jurisdiction of the Federal Shariat Courts in Article 203 (D).

This interpretation was first made in 1990 in the case of Darshan Masih v The State when the Supreme Court empowered itself by holding that it has the authority to take up matters addressed to it through informal complaints and on their motion. Before this, Article 184 (3) only allowed for cases to be heard under the larger umbrella of Public Interest Litigation which had to be filed by an aggrieved party to be heard. Now, because of this arbitrary and over-reaching interpretation, rules were made lax for such cases. Parties were no longer classified as either complainants, petitioners, or respondents, and the Court was empowered to make general recommendations to public bodies to enforce remedies. Several cases followed in which this newly invented jurisdiction was affirmed, and the Court has continued to assume the role of a benevolent guardian who conducts fact-finding missions and inquisitorially passes general orders for all stakeholders.

The event of a constitutional body originally devised to read the law for the adjudication of disputes, reading textually absent powers into existence, is of profound importance in Pakistani context. Not only does it signify the Court’s ability and penchant to create and extend its powers, but it also establishes the Constitution as a being that survives far beyond its physical manifestation – the text. More importantly, it distinguishes textual interpretation as a separate source of law, extending it far beyond its conventional role of being the process through which the law is derived. The vast and increasingly expanding gap between the text and the interpretation of Article 184 (3) of the Pakistani Constitution is the focal point of interest of this paper. This paper aims to scrutinise an oft-made assumption in the literature about Article 184 (3) powers in Pakistan – the Supreme Court’s power to hear cases suo motu, is constitutionally guaranteed despite its textual absence. To achieve this aim, this paper will primarily focus on the two textual requirements stipulated in Article 184 (3) of the Constitution – public importance and violation of fundamental rights.

The first part of this paper will compare currently existing literature on Article 184 (3) powers in Pakistan to highlight presumptions and theoretical lacunae. This part will focus on existing developments on the matter and distinguishing this paper from its predecessors. The second part of the paper will conduct a multi-tiered study of the history of the development of the textual requirements of Article 184 (3). This part will be divided into three sections. The first of which will track the jurisprudential development of the textual requirements in the pre-Darshan Masih era, which extends from 1973 to 1989. The second section will conduct an in-depth study of the Darshan Masih case, the political and judicial context of that time, and the facts surrounding the case, to ascribe reasons for a sudden shift in jurisprudence. This section will attempt to scrutinise the factors that may have contributed towards the relaxing of procedural requirements that are specific to Article 184 (3) and usual rules of procedure that includes requirements of locus standi, filing of petitions, and more. The last section of this part will study cases that extend from the 1990s to the activist tenures of the Chief Justices Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry and Mian Saqib Nisar. This section aims to identify and analyse the causes of the affirmation of the Darshan Masih ruling with regards to the subversion of procedural requirements and the impact it has had on the operations of contemporary Supreme Court tenures. The goal is to highlight that the Supreme Court has refused to revisit the 1990 ruling pertaining to the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3) and has assumed the validity of a non-textual interpretation as the law of the land.

The third part of the paper will aim to synthesise the data gathered in the second part and attempt to form a trajectory regarding the reading of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). This part will identify and elaborate upon the implications that a broad and invasive interpretation of this provision has had on governance and constitutional integrity. Amongst other ramifications, this paper will highlight how the current suo motu jurisprudence by Pakistan's Supreme Court violates the political question doctrine, the idea that courts have the authority only to hear legal and not political questions. Under the garb of public interest, the Chaudhry and the Nisar Courts have rendered the dichotomy between the legal and the political murkier than ever. Several matters decided under the Court’s suo motu jurisdiction either involve political questions or have inherently political implications. Secondly, this paper will contend that excessive use of this power results in a blatant disregard for procedure and the doctrine of separation of powers. The current Article 184 (3) jurisprudence has allowed suo motu cases to operate free from procedural limitations of not just petitioners and aggrieved persons, but many times even the precedents. It has also allowed the Court to enforce remedies that should ideally be engineered by the legislature and administered by the executive. The Court undermines the process and disturbs well-established principles of separation of powers, in the name of disseminating expeditious, and what often is a starkly populist iteration of what it deems to be justice. This section of the paper will further assert that the gratuitous exercise of this power has resulted in an increased reliance on not just non-democratic institutions, but also on unelected champions who wield powers that are largely unchecked and unaccounted for. Such a reliance leaves representative institutions with far less incentive to improve and the democratic process with insufficient time and freedom to foster an order in which un-elected messiahs need not enforce fundamental rights.

This paper is subject to several limitations concerning its design, research, and argumentation. The primary limitation of this paper is its inability to study the development of Article 184 (3) jurisprudence and its procedural requirements by tools other than case law analysis. All limitations that exist for papers that rely strictly on statutory and jurisprudential data stand true for this paper. The development of the thesis also makes use of several informal discussions with Supreme Court judges. However, their contribution is restricted to gaining clarity regarding the scope, nature, and direction of argumentation. Much of their contribution was made in the form of books and article recommendations that were used thoroughly in the writing process.

The development of this paper required an in-depth analysis of more than nine-hundred cases. However, not all the cases discussed and developed the meaning of the text of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). Hence, the scope of this paper is limited to the cases that pertained to questions of law regarding the text of Article 184 (3). Several cases, especially those decided after 1990, either do not discuss the satisfaction of the procedural requirements or assume that they are being met. Such cases are not relevant to the subject-matter of the thesis. This, however, does not mean that such cases have no substantive relevance for this paper. These cases will be used in the part that discusses the implications of the creation of expansive suo motu powers.

Literature Review

Since 1990, post-Darshan Masih period, a plethora of academic effort has been employed towards unpacking suo motu actions in Pakistan. Article 184 (3) of the Pakistani Constitution has been scrutinised in great depth with the more significant proportion of the work dedicated to contextualising the judicialisation of politics, and vice versa. Several papers on the issue trace the history of Public Interest Litigation to the Darshan Masih case and study its gratuitous application by the Chaudhry Court. Much work has been dedicated to understanding the nuances of the Supreme Court’s application of Article 184 (3), and the implications of the judiciary delving into political questions. Many scholars have also studied Article 184 (3) through the lens of the activism-restraint debate.

However, all papers and reports that were studied in preparation of this paper either tacitly or manifestly accept the validity of suo motu powers as a constitutional doctrine, despite its textual absence. Some authors criticise the judicial overreach that caused the creation of this doctrine, but most accept its constitutionality due to its invention by way of common law. Scholarship questioning the anti-democratic nature of the judicial creation of suo motu powers in the reading of Article 184 (3) is either completely absent or only tangentially referred to in relevant literature. One may ascribe the reasons behind this implicit acceptance to historical indoctrination of common law as a source of law and the seemingly corrective and pro-people nature of judicial powers under Article 184 (3).

This paper, on the other hand, attempts to question some of the most fundamental assumptions that are prevalent in the discourse on suo motu powers in Pakistan. Such an attempt is a novel contribution of this paper as already existing perspectives, albeit very effectively, provide analyses of suo motu on its merits, without studying the causes of its origins. Not only will this paper conduct a historical case law analysis of the development of suo motu in Pakistan, but it will also study the reasons that led to its extra-constitutional interpretation. While the importance of studying the merits of Article 184 (3) remains obvious, especially in the wake of the Nisar Court, it is also imperative to understand the statutory interpretational tools and their application that led to its creation. The novelty of this paper lies in its primary goal to study the interpretational tools for the creation and the affirmation of the doctrine of suo motu.

Development of Article 184 (3) Jurisprudence:

This paper divides the jurisprudential development of Article 184 (3) into three periods, the pre-Darshan Masih Period (1973-1988), the Darshan Masih case (1988-1990), and the post-Darshan Masih period (1990 onwards). The reason for this categorisation is two-fold. Firstly, the power of suo motu was assumed by the Supreme Court in 1990, in the Darshan Masih case, hence it serves as a reference point from which one may draw comparisons regarding the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3).

Secondly, as it will be elaborated upon below, these three eras are marked with distinct approaches that the Court has taken while interpreting Article 184 (3). The pre-Darshan Masih era is categorised with scepticism and restraint. The Supreme Court, in this era, questioned the scope of the procedural requirements stipulated in Article 184 (3) and often limited the scope of the provision. In the second phase, the Darshan Masih case, it is argued that the grave nature of the facts provoked the Court to subvert the procedure in favour of granting an expeditious remedy. This era marks a shift in interpretation, but also towards uncertainty, as no test regarding the application (or lack thereof) of the provision was developed by the Court.

Lastly, the third phase, the post-Darshan Masih era, is characterised as one that drew inspiration from the Darshan Masih case. However, it applied the rule regarding the relaxation of procedure to a range of cases. In this era, the Court has often either failed to satisfy the procedural requirements or has opted to disregard them entirely. At this stage, it is crucial to analyse the relevant cases in each of these eras to make conclusions regarding the evolution of Article 184 (3) procedural requirements.

I. Pre-Darshan Masih Era (1973-1988)

Article 184 (3) of the Constitution has been present in the text since its enactment in 1973. At this stage, this constitutional provision provided only a mechanism to pursue claims under the larger umbrella of Public Interest Litigation. As this paper will discuss, the power of suo motu came much later in 1990. However, the first case invoking the provision was heard by the Supreme Court in 1975, in the case of Manzoor Elahi v Federation of Pakistan. This being the first case of its kind, the bench led by Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman, only had the text of the provision to base their interpretation on. All three judges, including the Chief Justice Rahman, Justice Salahuddin Ahmad, and Justice Anwar ul Haq, concurred that the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court might only be invoked if “a question of public importance with reference to the enforcement of any fundamental right is involved.” The Court further ruled that if the matter before it is being heard by a court of concurrent jurisdiction (which in this case were the High Courts of Sindh and Baluchistan), the Supreme Court must refrain from passing an order and wait for the court with the concurrent jurisdiction to decide it first. The significance of this ruling is substantial, being the first-ever reading of Article 184 (3), the Supreme Court held that not only does a successful invoking of Article 184 (3), require that the procedural requirements be conjunctively met, it also requires that the same matter be not at issue at another court. It is imperative to note that none of the judges on the bench made even a tangential reference to suo motu powers or the subversion of standard rules of procedure.

The next instance when the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3) were directly in issue was in the case of Benazir Bhutto v Federation of Pakistan. In this case, Chief Justice Muhammad Haleem, before proceeding with his order, mentioned the satisfaction of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). According to the Chief Justice, Section 21 of the Representation of the People Ordinance 1985, the legislation under review was violative of the constitutional rights enshrined within Article 17 (2) of the Constitution. He further reasoned that an issue that concerns the political representation and the electoral process is a matter of public importance under the meaning of Article 184 (3) of the Constitution. Hence, the Court’s interpretation of the constitutional provision was in harmony with the text and the precedent set by the Manzoor Elahi case. This case consolidates the claim that in the pre-1990 era, the Supreme Court was more inclined to preserve and conform to the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3).

The next case in this era was heard soon after the previous case, in 1988. However, unlike both the previous cases, the Supreme Court reached a different conclusion regarding the application of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). In the case of Noor Muhammad v Federation of Pakistan, the petitioner sought for the judicial review of Section 11 of the Representation of the People Act 1976. The crux of the petitioner’s claim was that the First-Past-The-Pole system of voting, prescribed by the Act in question, had several defects, and democratic principles would be better served if a switch to proportional representation is made. Chief Justice Muhammad Haleem continued in his restrictive reading of the text of Article 184 (3) and held that the issue of the system of voting did not pertain to the enforcement of or constitute a violation of fundamental rights that are enshrined in the Constitution. He reasoned that because the claim fails to satisfy a procedural requirement and the matter strictly relates to the “legislative fiat”, the Court cannot assume original jurisdiction on the matter. The Supreme Court’s dismissal of this petition is significant because not only does this further narrow the scope of Article 184 (3), but it also suggests that if a matter relates to legislative power, then the Court shall not exercise its jurisdiction. The same outcome was witnessed in the case of Kabir Ahmad Bukhari v Federation of Pakistan, where the Supreme Court in a brief order dismissed a petition filed under Article 184 (3) as the petitioner could not establish a violation of fundamental rights, thus failing to satisfy a procedural requirement of Public Interest Litigation.

Similarly, in Muhammad Saifullah Khan v Federation of Pakistan, the Supreme Court remained persistent in its endeavour to strictly interpret the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). The Court held that the text of the Constitution is clear regarding the need for infringement of fundamental rights and those too that are present in the text of the Constitution. Hence, in the Saifullah Khan case, the Supreme Court affirmed that the original jurisdiction without the establishing infringement of fundamental rights is barred.

In this era, the Supreme Court continued to develop the procedure for invoking a claim under Article 184 (3). The general trend was that the Court exercised restraint and only allowed Article 184 (3) to be invoked where the petitioner strictly met the procedural requirements. This trend is apparent in what was arguably the last significant case on the provision in the pre-Darshan Masih era: the case of Cecil (Sohail) Chowdhry v Federation of Pakistan. In this case, the petitioner, a retired captain of the Pakistan Air Force, sought a judicial review of a political party’s manifesto on the ground that it “offends the very spirit of the Constitution” as it calls for a ban on non-Muslim being appointed in positions of authority. The Supreme Court, in this case, held that the text of Article 184 (3) is limited for challenging either enforced executive or legislative actions that violate fundamental rights. The Court was of the view that a political party’s manifesto serves merely as a public declaration and does not qualify as an action that may violate fundamental rights.

Moreover, the Court held that the existence of a disagreeable manifesto does not give rise to a cause of action or grievance under the meaning of Article 184 (3). Lastly, the Court opined that the mere existence of a disagreeable manifesto also does not satisfy the test of public importance as stipulated under Article 184 (3). This decision is significant for several reasons. Not only did it emphasise the need to satisfy the specific procedural requirements of Article 184 (3), that pertain to an infringement of fundamental rights and an issue of public of importance, but it also highlights the petitioner’s requirement to adhere to usual of rules of procedure. Such rules of procedure, which pertain to the existence of a valid cause of action, locus standi, and grievance, as this paper will later elaborate, were subsided in favour of an activist approach by the Supreme Court. This case marked the Supreme Court’s last major attempt to limit the scope of Article 184 (3).

II. The Darshan Masih Era (1988-1990)

The Darshan Masih case, also known as the “Bonded Labour Case”, is often cited as the turning point in Public Interest Litigation jurisprudence in Pakistan. While there is credence to this assertion, it remains vital to understand the authorities on which the Darshan Masih judgment relies. An analysis of such authorities allows us to have an insight into the context that led to the expansion in the scope of Article 184 (3). An example for such authority is of another Benazir Bhutto case of 1988. The reason for including this case in this section is that the Darshan Masih judgment relies primarily on the ruling of this case in its creation of the power of suo motu power. More importantly, this Benazir Bhutto ruling provides an in-depth insight into the political and judicial context in which the Darshan Masih case was decided.

In 1988, Benazir Bhutto challenged the constitutionality of the amendments made to the Political Parties Act 1962, and the Freedom of Association Order 1978 (then Presidential Order No. 20 of 1978). As the petitioner, she claimed that the aforementioned executive actions are violative of fundamental rights enshrined within Articles 17 and 25 of the 1973 Constitution. The petition included several other claims, including challenging the constitutionality of Article 270-A in violation of the concept of legal sovereignty and judicial independence. However, the significance of this case and its relevance to this paper lies in its relaxation of the procedural requirements stipulated in Article 184 (3) of the Constitution. The Supreme Court, in an unprecedented reading of the Constitution, decided to hold that the text of Article 184 (3) is “open-ended” and is not qualified by its procedural requirements. An eleven-member bench led by Chief Justice Muhammad Haleem relaxed several well-established principles regarding Public Interest Litigation in Pakistan.

The Supreme Court held that the requirement for the petition to be filed by an aggrieved party would be considered to have been met if the case is filed by a party that is under the risk of suffering from potential future harm. The Supreme Court, hence, decided that a petition invoking Article 184 (3) need not necessarily be filed by a party that already suffered a grievance and that traditional rules of locus standi may be dispensed with in favour of public interest if the person bringing the suit has a bona-fide interest. Furthermore, with regards to the requirement of having an infringement of fundamental rights, the Supreme Court held that it is not necessary that a violation of fundamental rights to have already occurred for a petition under Article 184 (3) to be maintained. As per the new ruling, the Court held that if an executive or legislative action has the mere potential of being discriminatory or violative of fundamental rights, the requirement may be understood to have been met. The petitioner merely needs to establish that the action is capable of being administered in a partial, unjust, and oppressive manner.

Moreover, the Supreme Court held that because the text of Article 184 (3) does not explicitly mention that standard rules of procedure would apply, the provision may be understood as one that is “open-ended.” As per the judgment, “the Article does not say as to who shall have the right to move the Supreme Court nor does it say by what proceedings the Supreme Court may be so moved or whether it is confined to the enforcement of the Fundamental Rights of an individual which are infracted or extends to the enforcement of the rights of a group or a class of persons whose rights are violated.” The Court strayed from the established rules regarding the provision and decided that the interpretation of Article 184 (3) ought not to be a “ceremonious observance of the rules or usages of interpretation.” Instead, the Court emphasised on the “object and purpose for which Article 184 (3) was enacted.”

The Supreme Court’s attempt at relaxing the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3) in this case becomes even more interesting when the statutory interpretation tools employed by the Court are studied. In its judgment, the Supreme Court made use of several interpretational tools. Firstly, the Court scrutinised the text of Article 184 (3) and opined that since the text of the provision does not explicitly mention that Article 184 (3) will be subject to conventional procedural requirements, the Court cannot assume that they apply. The Court buttressed this rather soft textual interpretation with an analysis of Article 184 (3)’s legislative intent. The Supreme Court was of the opinion that the framers of the provision would have expressly mentioned that Public Interest Litigation is constrained by the standard rule of procedure if that was their intent. As per the Court, the original intent of the provision does not appear to put “proceedings for the enforcement of fundamental rights in a strait-jacket”, instead it is essential for judges to set aside their fondness for the written word and precedent in favour of flexibility with regards to purpose. In its attempt to break away from established rules set by aforementioned cases, the Court states that judges ought not to become “mere slaves of precedent” and that “too rigid adherence to precedent may lead to injustice in a particular case and also unduly restrict the proper development of the law.” The Supreme Court had employed a variety of interpretational tools, to conclude that no limitations or conditions exist that may prevent a party from obtaining relief under Article 184 (3). The no “strait-jacket formula” applied by the Court, in this case, has had far-reaching consequences in the application of Article 184 (3) in Pakistan. It established the provision as one that confers on the courts the power to pronounce general decrees for the enforcement of fundamental rights without adherence to procedure. More importantly, it provided citizens with a forum aside from those causing the grievances themselves, for their redressal. A few months after the pronouncement of this judgment, which ironically discourages a rigid application of stare decisis, it was used as precedent, by three judges of the same bench. However, this time, the Court used it as a means of taking the expansion of Article 184 (3) one step further to empower itself with authority to hear cases suo motu.

On 30 July 1988, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan received a telegram signed by Darshan Masih along with twenty of his fellow brick kiln labourers, including women and children, praying for immediate help against the brick kiln owners. The authors of the letter claimed that the brick kiln owners had subjected them to severe and continuous unfair labour practices. It also sought help from the Court regarding the unfair arrest and detention of brick kiln workers by police officers who were operating in the interest of the brick kiln owners. The issues in front of the Court pertained to the existence of bonded labour and slavery in the brick kiln industry and the arrests of the bonded labourers by the Police. However, before these issues could be decided upon, the Court first had to decide a few procedural questions, some of which were unprecedented. Firstly, the Court had to decide on the validity of a telegram addressed to an individual judge, in this case, Chief Justice Afzal Zullah, as a proper mechanism of initiating a suit. Secondly, the Court had to identify a sub-provision of Article 184 under which such a suit, if accepted as properly initiated, could be maintained. Lastly, the Court had to decide on the method of gathering evidence that it could adopt and the nature of the remedy that it could provide under this petition.

The unprecedented nature of this suit allowed the Court to have ample amount of flexibility with regards to its reading of the law. For the purposes of the question regarding taking cognizance of a matter based on receipt of a telegram is concerned, the Supreme Court sought guidance in the text of Article 184 (3) and case law. The Supreme Court reasoned that the absence of a particular mechanism for accepting petitions for initiation of suits in the text of Article 184 (3) allows it to operate free from procedural shackles. As per the Supreme Court, because the text of the provision does not prescribe a method for the initiation of suits, the Court may entertain any method of initiation based on the gravity of the matter. In other words, the Supreme Court relied on its measure for what constitutes an issue of “public importance” to determine whether a telegram may be maintained as a valid method of initiating a case. Furthermore, the Supreme Court relied on the procedural relaxations allowed through the precedent set by the Benazir Bhutto case. The Supreme Court expanded upon the ruling by holding that telegrams may be accepted as a valid form of establishing cognizance of a case if the nature and gravity of the facts satisfy the test of public importance as defined in the vague and unrestricted Benazir Bhutto ruling.

Concerning the question of the nature of remedies that it may pronounce, the Court once again conducted what it deemed to be a textual analysis of Article 184 (3). The Court held that the nature and scope of orders that may be passed under Article 184 (3) is the same as that of cases being heard under Article 199, which deals with the writ jurisdiction of the High Courts. As per Article 199, any order may be given to direct any person or authority as “may be appropriate” and it “cannot be abridged or curtailed by the law.” Relying on the text of Article 199 to determine the scope of remedies given under Article 184 (3), allowed the Supreme Court to expand its discretionary remedial powers momentously.

Most importantly, and perhaps why this case is prominent, the Supreme Court decided that not only does Article 184 (3) allow it to have the power to gather evidence and summon parties inquisitorially, but it also allows it to have the power to hear and initiate cases on its own accord, which in Latin translates to “suo motu.” In an unprecedented and jurisprudentially unusual ruling, the Supreme Court reasoned that the cases of Public Interest Litigation “require more than legal scholarship and a knowledge of textbook law.” The Court dissociated itself from its conventional role of final arbiter in questions of law. It opined that depending on the circumstances of the case, it might assume the role of an organ of state that may identify violations of fundamental rights and conduct fact-finding missions for their alleviation. As already established by this paper, such a role had not been assumed by this Court in its history. The Court, however, remained adamant that in cases where violations of fundamental rights may be a possibility, subversion of the procedure is a necessary evil that needs to be committed.

The Darshan Masih case, while often considered to be the turning point in Article 184 (3) jurisprudence in Pakistan, was, in fact, a coup de grâce for the preservation of conventional rules of procedure in Public Interest Litigation cases. As this paper further elaborates, it opened the floodgates to petitions invoking the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction under Article 184 (3), which prior to 1988 was a seldom occurrence.

III. Post-Darshan Masih Case (1990-2000)

The Darshan Masih judgment’s most noticeable contribution to Article 184 (3) jurisprudence was that it minimised the discussion on the procedural requirements stipulated in its text in most future judgments. This section will highlight two noticeable patterns in cases following the Darshan Masih ruling. Firstly, it will underline the surge in the number of cases that was directly caused by the relaxation of the procedure. Secondly, it will highlight that after the Darshan Masih ruling, merely a handful of cases hinted at even the slightest discussion on the procedural requirements. The Supreme Court, with its expansive ruling, necessarily precluded the possibility of a jurisprudential curtailing of Article 184 (3) powers. However, to outline the process of the eventual affirmation of the Darshan Masih ruling, this section will shed light on the few cases that did attempt to discuss the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). At this stage, it is essential to note that this paper consciously excludes the discussion on Article 184 (3) cases heard during the tenures of the two most notoriously activist Supreme Courts Chief Justices in the history of Pakistan: Justices Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry and Mian Saqib Nisar. The rationale behind this exclusion is that cases from these two eras do not contribute to the substantiation of this thesis. Those cases assume the validity of suo motu powers and their emanation from Article 184 (3). More importantly, those cases do not attempt to discuss the satisfaction, or lack thereof, of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3). Hence, for the purposes of this paper, the Chaudhry and Nisar Courts are understood to be the result of the jurisprudential gymnastics employed by the Supreme Court in the late 1980s.

One of the few cases that elaborated upon the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3) was that of I.A Sharwani v Government of Pakistan. In this case, a group of retired civil servants and retired judges, filed a petition under Article 184 (3) of the Constitution, because they were being denied pension for retiring before a specified date. The petitioners claimed that such a denial violated their rights enshrined within Article 25 of the Constitution. The respondents claimed that the petition ought not to be maintained under Article 184 (3), as the petitioners have not exhausted all alternative remedies before approaching the Court. The Supreme Court, in this case, relied on the precedent set by the Darshan Masih and the Benazir Bhutto case to reiterate that the tests for public importance and breach of fundamental rights do not need to be rigidly met and found the petition to be maintainable on these preliminary grounds. However, in previous cases, even though the Supreme Court expanded the relaxed procedural requirements of Article 184 (3), it did so by increasing its reliance on the text of Article 199 of the Constitution. Article 199, which provides the High Courts to have writ jurisdiction for the enforcement of fundamental rights, requires petitioners to have exhausted all other remedies and fora before approaching the High Courts. If the Supreme Court is to rely on Article 199 for this reading of Article 184 (3), as per the precedent set by the Darshan Masih and Benazir Bhutto cases, principles of stare decisis dictate that it ought to require petitioners invoking its jurisdiction to have exhausted all other remedies first. However, in the I.A Sharwani case, the Supreme Court held that cognizance of matters might be taken under Article 184 (3), despite the fact that alternative remedies were available. The Supreme Court, in this case, persisted in its endeavours to facilitate rights enforcement against the preservation of procedure.

The cases following the I.A Sharwani ruling were observed to be noticeably generous with what qualified as an issue of public importance and a breach of fundamental rights. More strikingly, the number of cases that refrained from mentioning the procedural requirements surged. This pattern is visible in the case of Innayat Bibi v Issac Nazir Ullah, wherein a case that pertained to succession rights of women from religious minorities and the Supreme Court took cognizance of a matter. It pronounced a verdict under Article 184 (3) of the Constitution without providing reasons regarding the satisfaction of the procedural requirements. The judgment merely states that the Court deems the case to be “amply fit for exercise for the power to do complete justice,” as it is claimed by “female members of a minority community.” Similar outcomes were noticed in the Suo Motu Constitution Petition No. 9 of 1991, and Suo Motu Constitutional Petition No. 1 of 2000. In both cases, while the Supreme Court did not elaborate upon the reasons as to why the matter is of public importance and which fundamental right mentioned explicitly in the Constitution might have been violated, the Court took cognizance of the matters on its own volition without the existence of an aggrieved petitioner with locus standi. In the Suo Motu case of 1991, regarding public hangings provided by Section 10 of the Special Courts for Speedy Trials Act 1992. The Supreme Court opined that the public hangings “of even the worst criminals violate the dignity of man contained in Article 14 of the Constitution.” While in the Suo Motu case of 2000, that pertained to the government imposing a country-wide ban on political meetings and processions, the Supreme Court claimed that such an action would violate Articles 15, 16, 17, and 19 of the Constitution. In both cases, the Supreme Court took cognizance of the matter by a news item appearing in the national press. Not only was this method of initiating a suo motu action was novel in Article 184 (3) jurisprudence at that time, but it was also a substantial expansion on the method of taking cognizance by way of a telegram, as witnessed in the Darshan Masih case. In the Darshan Masih case, while the petitioner’s telegram was not the conventional method of invoking Article 184 (3), it did explicitly address the Supreme Court and asked for a remedy. In the Suo Motu Cases of 1991 and 2000, the news articles were neither written with the intention of addressing the Supreme Court, nor did they pray for remedies. The Supreme Court, however, through these two suo motu cases established that news items appearing in the press may be used as a proper method of taking cognizance of matters in Article 184 (3) of the Constitution.

In the post-Darshan Masih era, the scope of remedies available under Article 184 (3), as decided in the Darshan Masih case, was also affirmed in the cases of M. Ismail Qureshi v M. Awais Qasim and Human Rights Case No. 1 of 1992. In both of these cases, the Supreme Court relied on the Darshan Masih case regarding the question of the nature and limit of the orders that the Court may pass in the cases invoking Article 184 (3) of the Constitution. In the M. Ismail Qureshi case, the Supreme Court affirmed the Darshan Masih ruling by holding that “the only limit on the powers of the Supreme Court to pass orders is that they should be appropriate.” While in the Human Rights Case No. 1 of 1992, the Supreme Court reiterated that “there is no other limit or condition imposed on the Supreme Court except that the appropriate order should be for the enforcement of any of the fundamental rights conferred by Chapter 1 of Part II of the Constitution.” The deliberately vague use of the term “appropriate” allowed the Court not only to pass over encompassing and general orders but also has allowed the Court to assume the authority to direct the legislature and the executive to regard law-making actions, in the form of its orders. As it will be discussed in the next section, the implications of the Court expanding its powers have been substantial on not just the role of the judiciary in Pakistan, but also for the country’s democratic integrity.

Jurisprudential Trajectory & Its Implication on the Docket

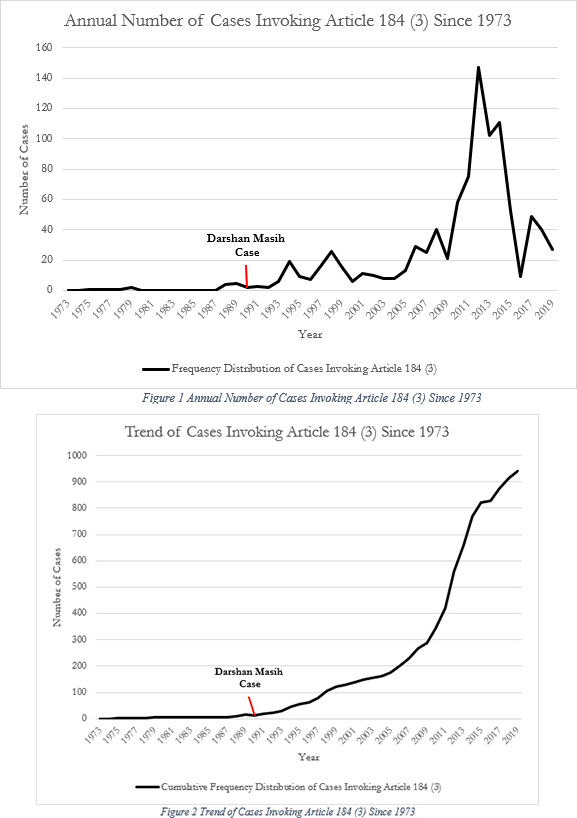

Since the promulgation of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan a total of 941 cases have been reported that invoke Article 184 (3). More interestingly, as depicted by Figures 1 and 2, the larger proportion of such cases started appearing on the Supreme Court’s docket after 1988, when the Benazir Bhutto case was decided, and then later in 1990 when it was expanded upon by the Darshan Masih case. From 1973 to 1990, the pre-Darshan Masih era, the Supreme Court decided a paltry total of 11 cases under Article 184 (3), an overwhelming majority of which were not found to have met the procedural requirements for maintainability. However, from 1990 to 2019, the Supreme Court decided a total of 930 cases invoking Article 184 (3), out of which most were found maintainable.

The comparison of the number of cases invoking Article 184 (3), in the pre and post Darshan Masih eras highlights the significance of the 1988 and the 1990 judgments. The trend substantiates a preliminary hypothesis asserted by this paper, that while the Darshan Masih case is a substantial event that greatly influenced Article 184 (3) jurisprudence, it by no means, ought to be understood as the catalyst that defined the current shape and form of Article 184 (3)’s reading. The onus for this change falls on the Benazir Bhutto case from 1988, which is relied heavily upon by the Darshan Masih case for setting the precedent pertaining to the subversion of procedure. However, the most striking surge in the number of Article 184 (3) cases was witnessed in 2009 and continued till 2013, during the Chief Justiceship of Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry and later from 2017 to late 2018 during the tenure of Chief Justice Mian Saqib Nisar. The two former Supreme Court Chiefs have been notorious for their trigger-happy use of suo motu powers, often without paying heed to the text of the provision, or any semblance of what remains of the procedural requirements. However, the two Chief Justices made novel contributions to Article 184 (3) jurisprudence by taking suo motu actions on issues that the Supreme Court’s interference was previously unheard of. Such issues include, massive population growth, taxation on cellular services, and even creation of a fund for the construction of dams. The two former Chiefs are often accused of employing their broad suo motu powers to take notice of and review any law, for the deploying of their own personal policy objectives. One may ascribe several motivations behind the populist endeavours made by both the Chaudhry and the Nisar Courts, to a multitude of political and personal ambitions. Motivations ranging from undermining of executive power in favour of the judicial supremacy, to more personal reasons pertaining to that of a legal messiah-esque legacy. This paper, however, perceives the Chaudhry and Nisar tenures as symptoms of the constructional expeditions embarked on to by the Supreme Court of the late 1980s. That is because the populist judges did little to either develop or restrict the jurisprudence pertaining to the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3), which is the core issue being studied in this paper.

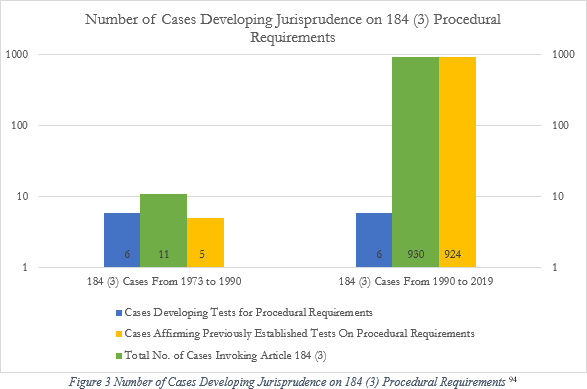

Figure 3 reveals an interesting pattern regarding the trend of the development of the procedural requirements in suo motu cases. For the purposes of clarity, it is important to mention that this paper considers those cases as ones that develop suo motu procedural requirements, which contain questions of law pertaining to the meaning and scope of the procedural requirements. Cases which include explanations, and ones that develop tests regarding the meaning of “public importance”, “infringement of fundamental rights”, and requirements of locus standi, public person, exhaustion of alternative remedies, and more. An illustration of such cases may be observed in Figure 3, which depicts the development of jurisprudence regarding the procedural requirements in Article 184 (3) cases, divides the available data in to two periods: The pre-Darshan Masih era 1973 to 1990, and the post-Darshan Masih era 1990 to 2019. The pattern of the development is nothing short of striking. Before between 1973 to 1990, a total of 11 cases invokes Article 184 (3). Six of such cases contained questions of law regarding the nature and the scope of the procedural requirements that need to be met. Five of the remaining cases, either do not contain such questions of law, or merely affirm the relevant rulings of previous cases. On the other hand, in the period extending from 1990 to 2019, a total of 930 Supreme Court cases that invoke Article 184 (3) have been reported. However, merely six cases delve into questions of law pertaining to the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3), while a momentous amount of 924 cases either simply affirm the relevant rules of previous judgments, or do not indulge such questions at all.

This trend vividly represents the influence that the jurisprudence expounded by the Supreme Court of the late 1980s has had on all future cases invoking Article 184 (3). It represents the Supreme Court’s inability to revisit jurisprudence that overtly results in the expansion of its powers. More importantly, it represents the Court’s penchant to justify its involvement in political questions and public policy matters. It also depicts the Supreme Court’s consistently selective reliance on stare decisis.

Conclusion

The implications of a broad an expansive interpretation of Article 184 (3), and the relaxation of its textual procedural requirements, extend far beyond the number of cases that the Supreme Court has had to entertain. Firstly, the interpretation has allowed the Court to extend its role from an arbiter of question of law to an arbiter of political questions. In other words, the current interpretation of the procedural requirements of Article 184 (3) results in the violation of the Political Question Doctrine. As per this principle of constitutional law, courts ought to strive to remain an apolitical branch of the government and refuse to hear issues that are either political in nature or have consequences that may be political. In recent history, the Chaudhry and the Nisar Courts have, under the garb of public interest, rendered the dichotomy between the legal and the political murkier than ever. Several matters decided under the Court’s suo motu jurisdiction are either overtly political or have consequences that cannot be separated from politics.

Moreover, as depicted in the previous section, the jurisprudential trajectory has allowed the Supreme Court to excessively employ its self-assumed suo motu powers. Such a generous practice of suo motu powers has signified the Court’s penchant to enforce remedies or call for actions that fall under the mandate of other state organs or enforce remedies that should ideally be engineered by the legislature and administered by the executive. The Supreme Court, through its benevolent use of Public Interest Litigation, often disturbs well-established principles of the separation of powers, in the name of disseminating expeditious, and what often is a starkly populist iteration of its own conception of justice.

Furthermore, when the subject matter of most recent suo motu case is perused, especially ones that were decided during the tenures of Chief Justices Iftikhar Chaudhry and Saqib Nisar, it is observed that a sizable portion of those cases pertain to matters in which judges lack the expertise to decide. In suo motu cases, in which the Supreme Court had ordered for the regulation of prices of goods, and establishing funds for the construction of dams, judges have assumed the role of not just public policy experts, but also as experts of professions that require in-depth technical knowledge. Not only does this encroach upon the mandate of institutions that are constitutionally authorised to make such public policy decisions, but it also risks half-baked implementation of unsustainable and poorly designed policy initiatives such as that of the dam fund.

Lastly, the unwarranted exercise of suo motu powers under Article 184 (3) additionally results in an increased reliance on not just non-democratic institutions, but also on unelected champions who wield powers that are largely unchecked and unaccounted for. The Supreme Court, under the misguided impulse of enforcing rights, has interfered with the democratic process of policy implementation far too often without cognizance of the fact that it perpetuates a cycle that stimulates the weakening of already feeble democratic institutions. Leaving them with far less incentive to improve and the democratic process with insufficient time and freedom to foster an order in which un-elected messiahs need not enforce fundamental rights.

This paper has attempted to explore the developments related to Article 184 (3) with the aim of identifying the various phases of progressive judicial approach of disregarding its procedural requirements in contemporary Public Interest Litigation jurisprudence. However, this paper puts an overt emphasis on the significance on the importance of procedure for the preservation of democratic norms and the smooth functioning of democratic institutions, it is yet to be discussed whether such a correlation stands true. Such a determination will have significant implications on how the jurisprudential trajectory laid down by this paper above is studied and how the role of the Supreme Court is perceived. The cultural and political indoctrinations that give rise to the arguments forwarded by this paper also require to be studied. However, if there is one determination that may be made with some degree of certainty it pertains to the obvious ineffectiveness of democratic institutions that has left a vacuum of power for the Supreme Court to occupy. Any future development of this paper will emphatically attempt to answer questions pertaining to the efficacy of having the debate on the origins (or lack thereof) of suo motu powers. More importantly, it will have to extend beyond jurisprudential and case law research and study more tangible variables to form a more vivid understanding of the implications of a disregard of procedure prescribed in the text of Article 184 (3).