Abstract

This article explains the special procedure laid down in Pakistani law for matrimonial cases. This extraordinarily quick procedure is distinct from civil law trial process. The article analyses recent cases of selected family courts to determine whether the official time frame for the disposal of family cases is followed in practice. The archival record of eight hundred and ninety cases were obtained from the family courts using convenient sampling technique. In addition, Family Courts judges were also interviewed. The main findings of this article are: first, the most prevalent type of cases are related to divorce; second, the fast-track procedure for matrimonial cases is difficult to follow in practice, nearly one-third of the cases (about 30%) took more than six months to complete, in contrast, two-third of the cases (about 70%) were completed within the time framework; and third, generally execution of decree takes more than six months to complete, with only three out of twenty-six cases completed within six months, as compared to the rest of the cases.

Keywords: Family Courts, Family Law Cases, Court Procedure, Delay in Court Proceedings, Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, Duration of Cases

Introduction

Severe matrimonial strife can cause couples to resort to one of the two options: i) resolve their issues, or ii) end their marriage by approaching courts. If couples choose to end their marriage, they may be faced with several legal issues related to dissolution of marriage through khul ‘(no-fault based divorce), Faskh (fault-based divorce) or restitution of conjugal rights and financial rights which include maintenance of wife and children, custody of children, payment of dower to the wife, recovery of dowry, and gifts or the return of dower to the husband. A speedy trial in such situations can be helpful in preventing a bitter and acrimonious divorce.

The main questions that are raised in this article are: what is the judicial procedure in Pakistan to adjudicate family cases; is it practical for family courts to follow a strict statutory time frame; what type of cases take more time to conclude; in which districts are family cases more likely to be expeditiously decided; what are the possible reasons for delay; and how the delay be further reduced?

Data was obtained to analyse selected family courts in Karachi, Shikarpur, Lahore, Sheikhupura, and Islamabad and the records were entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 23.0). Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for the purpose of data analysis.

Fast-Track Procedure and Slow-Going Results

A family law case is initially decided by the Family Court and any appeal may be filed before the first appellate court by either of the parties. Decisions of the first appellate court are often challenged through writ petitions in the High Court. In some cases, decisions of the High Courts are challenged in the Supreme Court of Pakistan. It is possible that the Supreme Court may remand a case back to the relevant High Court. However, in some cases, courts ignore the special procedure laid down in the Family Courts Act, 1964 (“FCA”). Therefore, it is necessary to mention the scheme of the Act which provides the fast-track procedure in family law cases. The preamble of the Family Courts Act 1964 provides that the Act aims at the “expeditious settlement and disposal of disputes relating to marriage and family affairs and for matters connected therewith.” In the schedule amended up to date, the matrimonial disputes include:

(i) dissolution of marriage [including Khula [khul ‘]],

(ii) dower,

(iii) maintenance

(iv) restitution of conjugal rights,

(v) custody of children [and visitation rights of parents to meet them],

(vi) guardianship,

(vii) jactitation of marriage,

(viii) dowry,

(ix) personal property and belongings of wife.

It is pertinent to note that before the promulgation of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961 (“MFLO”) and the FCA, cases pertaining to maintenance were dealt with by the Civil Court or Criminal Court. Before the promulgation of the FCA, wives had to, at times, wait for years to get divorced or to receive dower, dowry, gifts, or maintenance. They had to rely on the generosity of others in pursuance of cases. Even then, the amount they received at the end of often lengthy proceedings were insufficient. It was in this background that the FCA was enacted. The Act was further amended to curtail delaying tactics employed by husbands.

The relevant section under this Act is Section 12-A, which was inserted under the Family Courts (Amendment) Ordinance, 2002:

a Family Court shall dispose of a case, including a suit for dissolution of marriage, within a period of six months from the date of institution: provided that where a case is not disposed of within six months either party shall have a right to make an application to the High Court for necessary direction as the High Court may deem fit.

Section 14 of the Act made it mandatory for the Court of appeal to decide the case within four months. Under the newly added Section 17-A through the Amendment of 2002, the Family Court is under an obligation to pass an interim order directing the husband to pay interim maintenance allowance to the children and the wife after filing a written statement or at any stage thereafter. Section 21-A of the Act confers power upon the Family Court “to preserve and protect, any property in a dispute in a suit and any property of a party to the suit, the preservation of which is considered necessary for satisfaction of the decree, if and when passed.” In addition, under the 2002 Amendment in Section 25-B of the Act, orders of the District Appeal Court and the High Court staying the proceedings before the Family Court, shall cease to be effective on expiry of thirty days. Under the amended Section 10(4) of the Act, a Family Court is also empowered to instantly dissolve the marriage through Khula ‘when efforts for reconciliation fail.

Under Section 17 of the Act, provisions of the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, 1984 and Code of Civil Procedure (except Sections 10 and 11) are not applicable to proceedings before the Family Court. These provisions have an overriding effect on the judgment of any court. It can be concluded that the legislature has taken drastic steps to provide an expeditious and speedy procedure for family disputes at trial and appellate levels. It is in this background that a Divisional Bench of the Peshawar High Court held after reviewing the preamble, various sections, as well as amendments in the FCA that the legislative intent shows “that matrimonial disputes of all kinds specified/listed in the schedule by now are to be exclusively dealt with and tried by the Tribunal (Family Court) established and constituted under section 3 of the Act while jurisdiction of all other Courts, Tribunals including Civil Courts has been expressly ousted.” In another case, the Supreme Court held that “the Family Court where the wife resides shall have the jurisdiction to entertain such suits/claims.”

A full bench of the Peshawar High Court outlined the procedural law for matrimonial disputes and analysed important amendments in the FCA by stating that the “primary object behind such amendments obviously is to ensure quick disposal of such cases.”

Statistical Analysis of Cases Collected from Selected Family Courts

Archival records containing the list of cases, their types, dates of institution and disposal were obtained from various family courts of different districts using convenient sampling technique. The records were entered into SPSS (Version 23.0). Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for the purpose of data analysis. Descriptive statistics were utilised to determine the frequencies and proportions for the description of data on range of categorical (demographic) variables. While inferential statistics were used for the purpose of determining statistically significant relationships between different categories like districts, types of cases and duration of the case process. In this regard, chi square statistics were used.

These cases were instituted in the years of 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018. These cases were taken from different districts including Lahore (47.90%), Sheikhupura (21.20%), Karachi (12.10%), Islamabad (9.80%) and Shikarpur (9.00%) (See Table 1).

Proportion of Cases from Different Cities

Table 2: Frequency and Proportion of Types of Cases

Frequency of Range of Different Types of Family Cases Completed in 2017-2018

Table 2 represents the proportion of different types of cases. The most prevalent type of cases instituted was a wife’s unilateral right to no-fault judicial divorce – Khul ‘– (16.50%). The second most prevalent type of cases was Dissolution of Marriage – Faskh – (16.10%). The third most prevalent type of cases was Recovery of Maintenance (12%), followed by Restitution of Conjugal Rights (6.30%), Execution of Decree (2.90%), Recovery of Dowry (2.70%) and Cancellation of Decree (1.10 %). In contrast, cases of Restoration of Suits (0.70%), Custody of child (0.40 %%), Cancellation of Ex-Parte Proceedings (0.40%), Recovery of Dower (0.30%) and Review of Petition (0.10%) were least commonly reported (see figure 2 which represents proportion of cases excluding the missing archival record).

Duration of Cases

Table 3 represents the proportion of cases either completed within six months or after six months. Majority of the cases (70.93 %) were completed within six months as compared to the cases completed after six months (see figure 3). The difference between these frequencies/proportions is statistically significant as χ2 (df = 01) = 154.86, ρ = .00** (See Table 3).

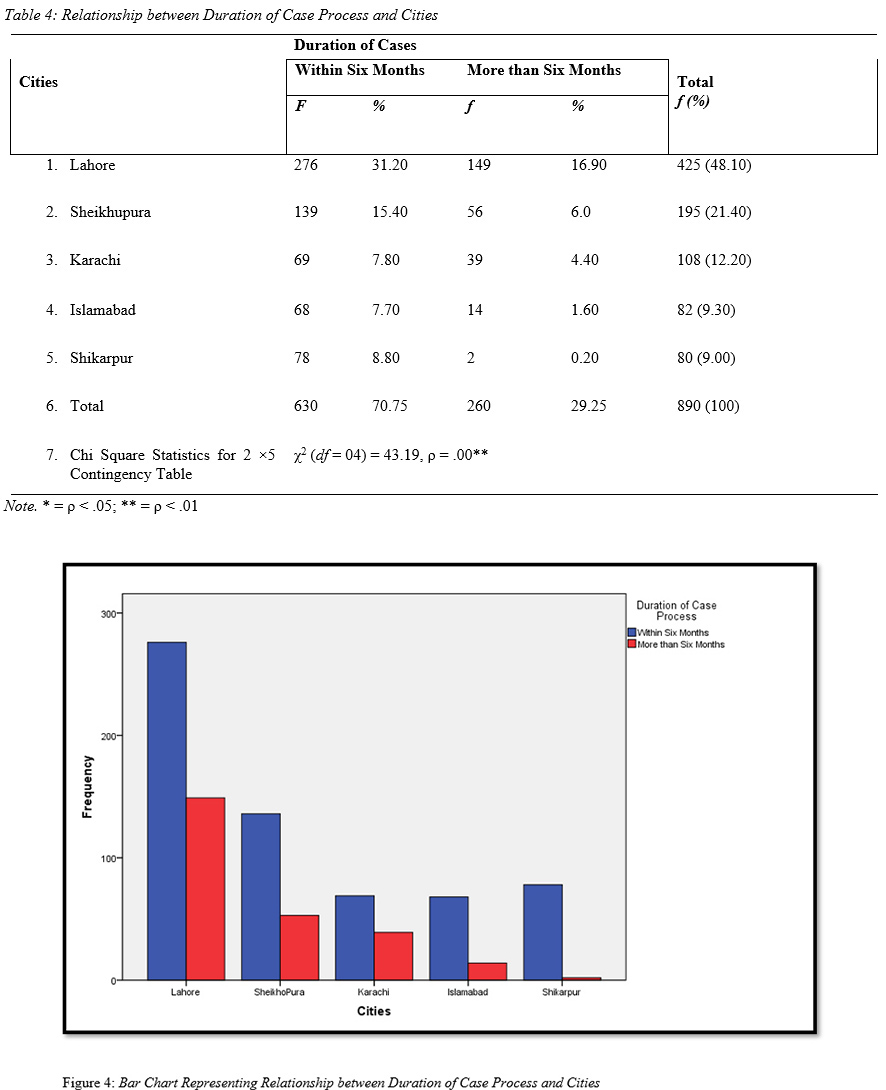

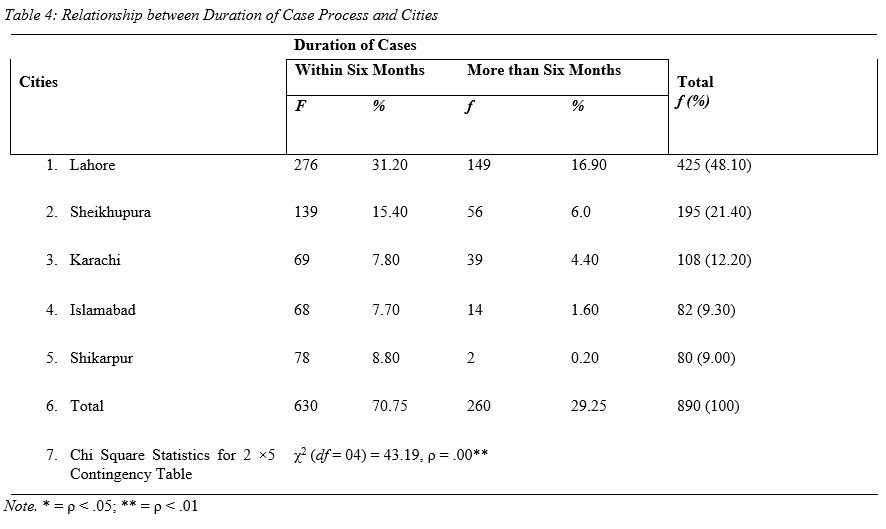

Relationship between Duration of Case Process and Cities

Table 4 represents the relationship between duration of case process and cities. Findings indicate that cases in Shikarpur are more likely to be completed within time (78 out of 80 cases completed within six months) as compared to the rest of the cities. In contrast, cases in Karachi are least likely to be completed within time limit (69 out 108 cases completed within six months) as compared to the rest of cities. This relationship between cities and duration of cases is significant as χ2 (df = 04) = 43.19, ρ < .01. Graphical representation of association between duration of case process and cities is given in figure 4.

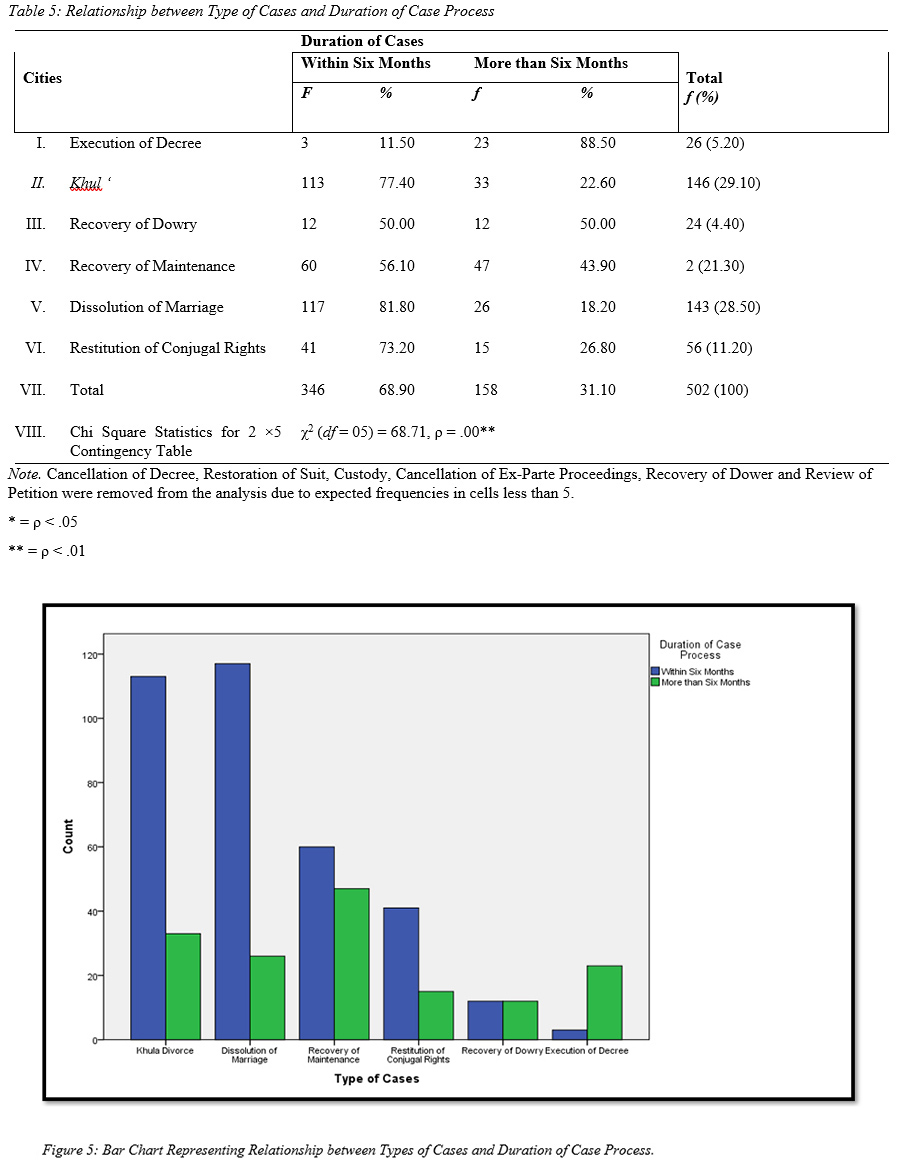

Relationship between Type of Cases and Duration of Case Process

Table 5 represents the relationship between types of cases and duration of case process. In most cases Execution of Decree generally takes more than six months to complete. However, rest of the types of cases including khul ‘, Recovery of Dowry, Recovery of Maintenance, Dissolution of Marriage and Restitution of Conjugal Rights are mostly completed within the six months.

Reasons for Delay of Disposal of Cases in Family Courts

It is imperative to note that the strict time frame is difficult to follow and about one-third of all family cases take much longer to conclude. There are several factors that contribute to the delays.

In the province of the Punjab the daily cause lists of Family Courts exceed 70 cases and it is simply impossible to effectively adjudicate them in the given time frame. The resulting backlog contributes largely to the delays. The transfer of presiding officers during the pendency of matters from one station to another and delayed replacement of new judges (who normally take time to get familiar with the new environment) also cause delay. Litigating parties are also to blame for the delays as frivolous case transfer applications are given to respective District Judges which result in interim orders. The concerned court then seeks comments from the Family Courts and replies and arguments from opposing parties are heard – which result in additional delays. In some instances, cases are transferred to a court that does not have jurisdiction, causing further delays in the process.

Moreover, cases may be transferred from one judge to another for administrative reasons. One reason for delays in Family Courts operating in larger cities like Karachi or Lahore is that there are many cases to deal with on daily basis as compared to less populated cities such as Shikarpur and Sheikhupura. Another reason is that, in some cases, the address of parties, especially that of the husband given to the Family Courts, is incorrect causing the summons not to be served. Additionally, in a few cases, the summons is sent on the home address of parties, which at times exists outside of the district or even the province. In such cases, the summons is sent by the court to the District and Session Judge of the relevant district and the process is thereby lengthened. Furthermore, in some cases, the party summoned works or resides abroad or in another city and is unable to attend the court on time and the only way is to request their counsel to get adjournment of proceedings to a date of their convenience. Similarly, new counsels are produced before courts who request adjournments to prepare the case. Moreover, in some cases, before the judgment is pronounced by the court, the counsel of the party who is not paid requests the court not to pronounce the decision.

Since the disposal of cases carries points, judges’ own priority for speedy disposal of cases might overlook justice. Certain cases are remanded by the superior courts after prolonged period of time to the trial court or to the first appellate court with a direction to decide them in a fixed time period. Such cases are treated as ‘Direction Cases’ and are taken up on a priority basis. But they push other cases behind. Since no appeal is allowed against an interim order, any aggrieved party may resort to the High Court invoking Article 199 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973. Though writs against interim orders are often not entertained, there are many cases in which these may be. Proceedings before the High Court take several months. Strikes by Bar Associations, leave of absence by presiding judges, and adjournments by counsels on both sides also contribute to delays in adjudication. Lawyers use various delaying tactics which include delay in submission of reply, non-availability of witnesses or documentary evidence, and non-production of witnesses for cross-examination.

Delays in family cases could be further reduced by making the process of Alternative Dispute Resolution or ADR mandatory. It is interesting to note that a kind of ADR already exists in Sections 10 and 12 of the FCA. Section 10(3) provides that “at the pre-trial, the Court shall ascertain the points at issue between the parties and attempt to effect a compromise or reconciliation between the parties, if this is possible.” This provision could be amended to make the efforts of compromise or conciliation mandatory at the pre-trial stage. At the moment, this provision is not applied as such because there is no compulsion for the courts to do so. Section 12(1) of the FCA may not be that important as it calls for compromise or reconciliation “after the closure of evidence of both sides”. A slight amendment in Section 10(3) could further speed up the process if attempt at reconciliation between the parties is made mandatory for the court. In other words, the Court shall act as a conciliator or an arbitrator to bring in reconciliation or reach a quick outcome either before or after ascertaining the issues. The choice whether the judge should act as a conciliator, or an arbitrator be left to the parties. Whatever the parties chose would be informally but instantly arrived at by the conciliator/arbitrator. Parties will save both money and time and will have their internal family issues quickly resolved in a confidential manner. Adjudication may only be used as an alternative and not as the primary way of resolving family cases. This is in harmony with the Qur’anic commandment in which Allah says, “If you fear a breach between the two, appoint an arbitrator from his people and an arbitrator from her people. If they both want to set things right, Allah will bring about reconciliation between them. Allah knows all, is well aware of everything.” It is noteworthy to highlight those efforts of the Arbitration Council, constituted under Section 7(4) of the MFLO, do not and cannot result in reconciliation because of the flawed nature of the provision.

On the other hand, reconciliation mentioned in Section 10(4) of the FCA in cases of khul‘ must be taken seriously at least in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) where the Peshawar High Court while deciding Fakhar-ud-Din v Kauser Takreem made reconciliation attempt by the Family Courts mandatory, and has laid down detailed procedure to affect the same. It would have been even better if the High Court would ask the legislature for an amendment in the law to the effect that the court should act as a conciliator or arbitrator (as the parties choose), which would not only keep the family issue private but would also save time and money for the parties. In addition, the parties would avoid the disadvantages of adversarial procedure. Finally, after lengthy discussions with many judicial officers from Sindh, Punjab, KPK, Baluchistan and Islamabad regarding improvements in decisions in matrimonial cases, I have concluded that only experienced judicial officers such as Additional Sessions Judges or at least Senior Civil Judges should exercise jurisdiction in family cases, which is now the exclusive domain of Family Judges. The latter are new appointees with either little or no legal experience of issues arising from marital life. However, such a change could only be done through legislation by all the provinces as well as the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT).

Conclusion

The legislature has provided a strict and fast-track timeframe in statutory laws of Pakistan with the disposal of family law cases. An analysis of the sample of 890 cases obtained from Family Courts in Karachi, Lahore, Shikarpur, Sheikhupura, and Islamabad suggests that the most prevalent form of cases in family courts relate to khul ‘and Faskh and the least common to Execution of Decree. Furthermore, while about two-third of family cases are disposed of within the statutory time frame of six months, one-third of such cases consume a longer time period. Some of the main contributing factors causing procedural delays in more populous cities pertain to the significant workload of Family Courts as compared to rural areas, incorrect addresses of the party provided to the courts, the party summoned living out of the district or the province, party working abroad or in other cities, appointment of new counsels who request for adjournment, and non-payment of lawyers’ fees. Due to the factors explained above as well as other issues, the strict time frame is difficult to follow in matrimonial issues.