Abstract

In the current day and age, data protection and digital privacy are used interchangeably. With modern technology and tech giants constantly and blatantly violating the privacy of individuals, the need for data protection measures and appropriate frameworks is continuously increasing. In such circumstances, developing nations like Pakistan, which currently do not have an appropriate legal framework for the regulation of big data hoarding companies, are at a major risk of being exploited. This Article focuses on the broader constitutional framework of privacy in Pakistan along with associated legislation. The paper then delves into the current framework of data protection in Pakistan and ultimately discusses the steps regulators are taking with respect to data protection, for example, drafting the Personal Data Protection Bill 2021. The paper further engages in a comparative analysis of data protection laws enacted by the pioneers in the field of digital privacy, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) of the European Union (“EU”) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (“CCPA”) of the United States of America (“US”), for a better understanding of the development of data protection laws in Pakistan. The detailed analysis of foreign as well as domestic approaches and theories yields a way forward, which would be more suitable to the demands and capabilities of Pakistani regulators and consumers.

Introduction

Privacy as a concept has become indispensable in this day and age. The developed world struggles with understanding and enforcing the right to privacy. In such a situation, third-world countries face the larger peril of being blithe about the threats posed by ineffective safeguards to their citizens’ right to privacy. Although the factors impacting the right to digital privacy are uniform around the world, the safeguards against them are strikingly different. These differences make the discussion about developing nations like Pakistan crucial.

Pakistan guarantees the right to privacy and dignity to its citizens under its constitutional framework. Under Article 14 of The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 (“Constitution”), “the dignity of man and, subject to law, the privacy of home, shall be inviolable.”1 It is clear that the right to privacy under the Constitution is subject to certain limitations; various caveats arise from interpreting the right to privacy in light of digital spheres by virtue of the right to privacy not being an absolute right. First and foremost, what constitutes the state’s right to intervene in a citizen’s privacy is vital to the discussion. It is only when state limitations in the physical world are understood that they can be extended to private parties in the digital sphere. Privacy, as a right under the Constitution, requires additional theorisation on jurisprudential grounds.

Important Court Rulings on The Right to Privacy

The right to privacy as a fundamental right, along with its limitations, has been discussed in numerous leading cases in Pakistan. Although the cases have mainly dealt with the right to privacy regarding state intervention, they set some very important general principles.

I. The Privacy of “Home” Paradox

The first leading case in this regard is Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto v. President of Pakistan.2 This case discussed the question of privacy in the context of state intervention in the form of intercepting calls of public servants. The Court discussed the right to privacy and the factors impacting it under the constitutional provision on the right to privacy. Article 14 provides protection to the “privacy of home.” Justice Saleem Akhtar was of the view that the word “home” is not to be taken in its literal sense, rather, it is to be construed in a manner that broadens the scope of the provision.3 The Court relied on the leading judgment of the US Supreme Court in Katz v. United States,4 which extended the meaning of home as mentioned in the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution. In Katz, the US Supreme Court held that the phrase “privacy of home” shall be interpreted in a liberal and broad manner. Relying on Katz, Justice Saleem Akhtar in his concurring opinion has held the following in the Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto case:

[T]he dignity of man and privacy of the home is inviolable, it does not mean that except in home, his privacy is vulnerable and can be interfered or violated.5

In the Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto case, the Court highlighted the importance of the fundamental right to privacy by interpreting it alongside the fundamental rights to the inviolable dignity of a person and freedom of speech and stated that an intervention in the life of a person is a hindrance to a person’s right to speech.6 This particular issue is important in the context of digital privacy since it is in direct connection with speech and expression, which causes broader privacy concerns to the identity and behaviour of a person. The Court also reads the right to life provision, enshrined in Article 9 of the Constitution, in conjunction with Article 14. Article 9 reads that “no person shall be deprived of life or liberty save in accordance with the law.”7 The Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto case is a substantial addition to the jurisprudence on Article 14 as it has broadened the scope of the provision, including all places where a person reasonably presumes to be protected from invasion. Furthermore, multiple rights were amalgamated with Article 14 to expand its interpretation and to highlight its importance within the fundamental rights. This case relied upon in an important judgment of the Pakistani Supreme Court – Kh. Ahmad Tariq Raheem v. Federation of Pakistan.8

In the Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto case, the Court held that the state’s action of surveillance was not only unconstitutional but also a blatant disregard of the principles laid down in Surah Al-Hujurat of the Holy Qur’an.9 Article 227 of the Constitution provides, “All existing laws shall be brought in conformity with the Injunctions of Islam…”10 Therefore, while holding that a disregard for one’s privacy is a disregard of Allah’s commandments, the Court consequently held that any future law or action by the state or any private person which infringes upon one’s privacy would be unconstitutional under Article 227 of the Constitution.

II. Privacy Being Subject to Law

Despite both aforementioned cases giving a broad recognition to privacy, Article 14 itself is restrictive and does not outright regard privacy as an absolute right. The phrase “subject to law” is important in Article 14. However, the extent to which the exercise of the right is restricted needs to be examined.

Most restrictions apply to the extent of state interventions. However, their analysis highlights important jurisprudence for application to private bodies. In Riaz v. Station House Officer,11 the police conducted a raid on a purported brothel after obtaining a warrant under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (“CrPC”),12 and caught two people committing Zina. In this case, the Magistrate issued a warrant without due consideration and in a mechanical manner, without considering the sensitivity and merits of the matter. Resultantly, the Court held that the Magistrate was wrong in awarding a search warrant in a mechanical manner as the privacy of the home of a person is constitutionally protected. Therefore, an instrument of a search warrant being powerful enough to allow infringement of one’s privacy must not be given in a mechanical manner without due consideration under statutory provisions of the CrPC.

Interestingly, this decision has been upheld in numerous other cases which further highlight the importance of this constitutional right. In these cases, the defendants were found committing Zina — a Hadd offence and strictly punishable under Sharia. The courts were, however, adamant about considering the point of privacy and gave it primacy over a Hadd crime. In Zeeshan Ahmed v. The State,13 the Court held a raid conducted without a warrant to be unconstitutional and illegal. Furthermore, the Court cited two verses of the Holy Qur’an to highlight the importance of the right to privacy in Islam. Similarly, in Nadeem v. The State, Justice Khurshid Anwar Bhinder stressed the significance of the right to privacy by invoking Islamic teachings and principles. Justice Bhinder quoted the following Hadith in the Judgment:

[H]oly Prophet (peace be upon him) had said that if you go to somebody’s house knock the door once and if there is no reply knock it again and if there is no reply knock it for the third time and if still there is no reply, then do not try to enter the house and go back.14

By granting bail and requiring more inquiry, the Court stressed upon the importance of the right to privacy of home, not just under the constitutional framework but also under the Islamic principles.15 This reasoning was similarly upheld by the Balochistan High Court in Ghulam Hussain v. Additional Sessions Judge, Dera Allah Yar,16 thereby giving the phrase “subject to law” a very limited and specific interpretation.

Justice Qazi Faez Isa (as he then was) built on the above two principles and held that the right to privacy of the home does not restrict itself to the home only; instead, people, even in public spaces, have the right to limited privacy to the extent that it can be ensured.17 Given the foregoing discussion, it can be argued that the courts have given a very specific and limited interpretation to the phrase “subject to law” and a broad one to the “privacy of home.” The foregoing discussion sets the ground broad and fertile enough for the creation and enforcement of the right to privacy against big technological private companies.

Why Regulate Big Data and Big Tech?

Big data hoarding technological firms started emerging without any regulation from state bodies and continued operating for a long period till users and officials realised the harms associated with them. This section of the paper discusses the harms associated with big tech and big data and why it should be regulated, with the era of self-regulation finally coming to an end.

Zuboff theorises the emergence of tech corporations as part of the power structures. She states that these corporations started off with a balance of power in contrast to their users. The feed-back loop or the recursive system placed the user and the company at an equal power scale with both learning from each other.18 However, as time passed and with the advent of personal advertising, these tech corporations morphed into power and capital hungry entities. Instead of storing data generated by users into random sets, the corporations indulged in user profiling.19 The data that users provided was intentionally stored, associated, and permanently glued to the user and later manipulated in various ways.20 This created a power imbalance. This was highlighted in the case of Target Corporation wherein it was able to accurately predict that a woman was pregnant merely from the products that she purchased.21 The researchers at Target were able to predict this by looking at the shopping habits of the customers: it was observed that women who were pregnant often bought scent free lotions and that during the first twenty weeks of their pregnancy, they bought calcium, magnesium, and other supplements.22 This predictive power of corporations shook people to their core. A realisation sprung from this case that these corporations have become too powerful. Regulators and users realised the amount of information that was being collected and processed—all with their consent. Understanding the implications of this interplay between consent, information, and power imbalance is crucial in the modern-day world.

I. Information Asymmetry and the Issue of Consent

Information asymmetry is defined as the “information failure that occurs when one party to an economic transaction possesses greater material knowledge than the other party.”23 In the case of big tech and big data, this is relevant because these platforms operate on a notice‐and‐choice model. “Notice and choice” is the current paradigm for securing free and informed consent to business’ online data collection and use practices.24 The platform provides users with a consent form which, in strict terms, informs them that their information will be taken, stored, and used in a particular manner. The visualisation of terms by the platform serves as a notice; the acceptance of such terms is the choice of the user.25 States have not intervened with this approach primarily to “facilitate autonomy and individual choice.”26 Furthermore, notice and choice are more than just contractual tools for the transfer of information: they embody the principle of privacy as well.27 The model is based on the idealistic conceptualisation that platform visitors can give free consent and that “the combined effect of individual consent decisions is an acceptable overall trade-off between privacy and the benefits of information processing.”28 The efficacy of this approach, however, is questionable because of the complexity of the notice and choice model.

This approach is based on the idea that consumers are rational, and that they diligently read the terms set out by the platform, making them informed decision makers. There are, however, several caveats to this approach. The notices are written in a complex, wordy, and tautological manner. Even for those who read these terms, it is difficult to comprehend them effectively.29 And it is common for users to accept the terms without even reading them.30 This is primarily because of well-documented cognitive biases and the complexity of the ecosystem that people are placed within.31 Figure 1 shows the results of an online survey conducted independently for the purposes of this paper, which yielded more than two hundred responses. The participants had completed at least a bachelor’s level education and were regular users of digital platforms. In the survey, people were asked whether they read the privacy policies of the platforms they use. A majority responded that they either partially read the privacy policy, or do not read it at all. This implies that people are partially or entirely unaware of the terms they agree to when using a platform, putting themselves at a disadvantage when they are unaware of what data is being collected, processed, or stored, and how it is being used further for other services or businesses. This creates a power imbalance and an information asymmetry between the parties involved, with the platforms having an unfair advantage.

Figure 1: Percentage of users who read privacy policies completely, partially, or not at all.

The question arising here is whether such consent can still be regarded as free. Legally, it is regarded as free and informed consent since contemporary jurisprudence states that when the user has hypothetical knowledge of the platform and its services, it counts as informed consent.32 This approach is extremely questionable in the case of online contracts as they heavily favour one party while putting the other at a disadvantage with no bargaining power. The contemporary jurisprudential approach to this matter is not adequate for the protection of a person’s rights. Margret Jane Redin, a professor of law at the University of Michigan Law School, argues that only true and full knowledge of something can count as free and informed consent. Since non-readers cannot have complete information of the platform or its processes, their consent cannot be construed as free and informed.33 This can at best be regarded as “passive acquiescence.”34 Furthermore, since the services provided by these platforms have become a necessity in today’s world, users do not have much choice. Moreover, they cannot choose another service provider as all the service providers typically use the same framework. Therefore, users with practically no bargaining power cannot get a favourable contract from these platforms. Hence, the contracts are lopsided and highly favour the platform while keeping the users behind a veil of privacy.

Users, when signing up for services and upon seeing “the term ‘privacy policy,’ believe that their information will be protected in specific ways. They assume that a website that advertises a privacy policy will not share their personal information.” However, this is not the case; privacy policies often serve more as liability disclaimers for businesses than as assurances of privacy for consumers.35 The concept of information asymmetry is relevant here as well since the platforms are generally more aware of the terms that people consent to and hence, they can benefit from those by essentially limiting or excluding their liability. So, where the platforms show their users that they are concerned about their privacy, they typically engage in liability excluding practices by incorporating privacy infringing clauses – essentially exploiting the users’ cognitive biases and their own greater bargaining power and control through a lack of transparency and opaque platforms.

II. User Profiling and Predictive Exploitation

The notice‐and‐choice model, with its disclaimers and liability excluders, obtains the assent from users for data processing as well. Whereas consent ensures that people give access to their data, the actual processing of this data is the primary exploitation that big tech corporations indulge in. This directs the discussion towards the second issue under contention: the profiling of users.

Sofia Grafanaki, a privacy expert who writes extensively on data protection, terms this as the “context” 36 in any inquiry. This concept will be relied on later in this paper. Profiling is essentially the attachment of any information that can be used to identify a user. Furthermore, “once any piece of data has been linked to a person’s real identity, any association between this data and a virtual identity breaks the anonymity of the latter.”37 Another issue of data management is that data has an incremental effect: data tends to build on layers as more information is acquired, processed, and stored. A person may search for a query at one time using different keywords in a specific order and change them during a later search query. The processing of both these types of information will be different, yet the conclusion drawn by the algorithm will be attached to the user. With each layer of data added to a stream, it becomes increasingly revealing.38

One of the two-pronged issues of profiling is visualised when data sharing is considered critically. Generally, data administrators are involved in the practice of keeping data anonymous and sharing it with third parties. The data — immense and multi-layered — is susceptible to being used for re-identifying individuals. Administrators generally agree that such is the case. Google, one of the biggest data hoarders, made a statement, “it is difficult to guarantee complete anonymization, but we believe these changes will make it very unlikely users could be identified…”39

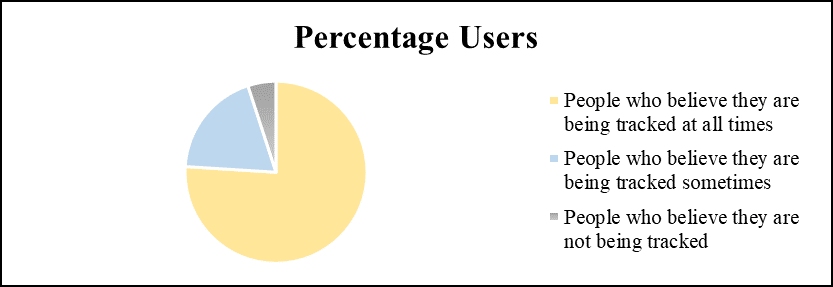

Profiles are used for predictive analysis and automated decision making for individuals, which ultimately raises concerns about privacy, discrimination, self-determination, and the restriction of options.40 The predictive analysis is based not on what the person needs or wants to see, but on what the algorithm thinks the person needs to see.41 This strips away a person’s autonomy in decision making. It is particularly crucial when considering news and the type of information passed on to individuals based on their ‘previous likings.’ This was highlighted in a widely popular case of Cambridge Analytica, in which the company had to face severe consequences. The case involved the consultancy firm Cambridge Analytica, which used the data of around 87 million Facebook users to advertise the US elections in favour of Donald J. Trump.42 Facebook, being able to track users across websites, procured information on people’s biases and interests and delivered election advertisements to voters.43 Segmentation in ads allowed the consultancy firm to “pigeonhole individuals into pre-determined categories”44 and “the automated decision making compartmentalised society into pockets”45 of people that either supported or opposed Trump. In addition to that, Trump supporters received advertisements with information about polling stations.46 Advertisers profited from user profiling and impacted the elections. This case received significant attention, even though predictive exploitation occurs every day with the misuse of user’s information, behaviour, and their conjecture with other like-minded individuals. Figure 2 shows the results of a survey asking users if they feel, from the content they view on platforms, that their internet activity is monitored across websites and platforms. The results were worrisome, with more than 75% of survey participants answering in the affirmative.

Figure 2: Percentage of users who believe their online activity is being tracked either all the time, some of the time, or not at all.

Referring to the concept put forth by Grafanaki, for a platform to work properly, it needs to understand two things. Firstly, the context of an inquiry or search. The context can be obtained by collecting the user’s previous data and its subsequent processing. According to Grafanaki, this formation of context creates the issue of privacy,47 as discussed above. Secondly, for platforms to work effectively, the relevance of what is presented to the user is required. This aspect of platform functioning creates challenges to autonomy.48 For more relevant results, platforms need to have the most recent knowledge of a user’s presence on the platform. Therefore, making their experience more relevant to their context whether it is in the form of results to their inquiries or advertisements. Based on this, a platform “assumes that users will continue to want the same thing they wanted in the past and will follow the same behavioural patterns. It also assumes that users will want the same as other people with similar traits. Whether the context of the inquiry is news, politics, or retail, the key to personalisation is that the results are relevant to the user.”49

The actions of a digital platform and users’ engagement create a reinforcing loop. This occurs as the act of clicking on a result or advertisement by a platform, influenced by the user’s context, serves to validate its relevance for them; “therefore, in the eyes of the algorithm, the user will want to see more of the same content.”50 Using this reinforcing loop, digital platforms are able to keep their in a constant back and forth flux of information. Past surveillance primarily guided the actions of the subjects, whereas contemporary surveillance is for capitalistic gains by keeping the person within the loop and using the data to slightly change opinions and create biases, as was seen in the Cambridge Analytica case.

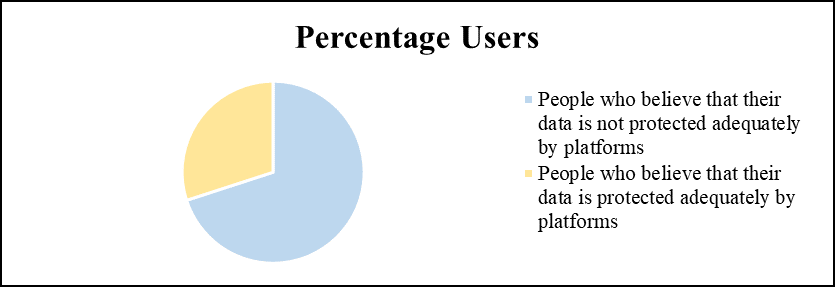

Due to the various reasons for information asymmetry, including inadequate consent; lack of transparency in data collection and processing, user profiling and its exploitative aspects, the widespread use of platforms for control and surveillance, the involvement of platforms in illegal activities such as elections, illegal or uninformed sale and transfers of data, and other issues such as data breaches and wilful leakage of databases, nations worldwide believe that stringent governmental control should be imposed on big data and tech firms and corporations. Figures 3 and 4 show the results of an independent survey for the purposes of this paper. The users were asked if they believe that their data is protected adequately by these corporations or not and if they must be regulated by the states. A significant majority of 93% agreed that these corporations must be regulated under data protection law. Thereby, all countries are considering such regulations,51 with the United States of America and the European Union currently in the lead by already having enforced regulations against the aforementioned entities.

Figure 3: Percentage of survey participants on whether their data is protected by platforms.

Figure 4: People who believe big tech corporations must be regulated.

A Comparative Analysis of Digital Privacy Laws of the US and EU

The standard data protection framework of the world is mostly governed by the European Union (“EU”) and the United States (“US”) laws on digital privacy. The EU is a global leader and the hub of data protection as it has always been taking the initiative in enacting data protection laws according to the changing times. In the EU, the concept of privacy emanates from the Charter of Fundamental Rights (“CFR”) as it is considered to be a fundamental right that cannot be violated. Additionally, the EU considers privacy law as “data protection” and the whole privacy regime of the EU revolves around the idea that data protection is a fundamental right guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights as well as the EU Charter,52 as mentioned above. The EU started enacting data protection laws in the early 1970s but the first comprehensive and exhaustive law applicable throughout the EU was the 95 Directive53 enacted in 1995.54 It was enacted to regulate the transfer of personal data of natural persons to third parties and countries outside the EU and to harmonise the data protection laws throughout the EU.55

However, in the US, the concept of privacy comes from the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution. Unlike the EU, the US did not have a holistic data protection law. In fact, the US deals with issues pertaining to data protection on a sectorial basis,56 and different states have enacted their own data privacy laws. Moreover, data processing and transferring of personal data is regulated by both the federal government and state laws in the US.57 The federal laws only cater to the security category of data protection for specific sectors like healthcare, financial data, and consumer information.58

The US and the EU have long been each other’s biggest trade and investment partners. The 95 Directive of the EU limited the transfer of personal data of EU citizens to third-party countries which did not offer adequate protection of data under their domestic laws.59 The US lacked comprehensive laws for data protection, hence it negotiated the Safe Harbor Agreement with the EU in fear of sanctions under the 95 Directive. The agreement stated that the US would be safe from any action by the European data protection authorities if it provided adequate protection of data being transferred to US companies by the EU. It also stated that the Federal Trade Commission of the US will take action against companies not complying with the agreement.60 The Safe Harbor Agreement remained effective until invalidated by the European Court of Justice through the Schrems Judgment.61 Schrems v. Data Protection Commissioner62 clarified that the 95 Directive was inadequate and a replacement of the Safe Harbor Agreement. The EU-US Privacy Shield was agreed between the countries to allow US companies to continue transferring and processing the personal data of EU citizens until the General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) came into force in 2018.63 The GDPR replaced the 95 Directive and was “set to allay European concern about how U.S. companies handle private data. Under the GDPR, US companies were expected to fully comply with much more restrictive privacy laws or face steep fines.”64 The enactment of the GDPR influenced many countries to come up with their own data protection laws. The US was especially bound by its relationship with the EU and hence, came up with the California Consumer Privacy Act (“CCPA”) just two months after the enactment of the GDPR. The CCPA is the most exhaustive and ambitious law on digital privacy in the history of the US.65 The US was also compelled to enact a comprehensive law after the Cambridge Analytica incident in which “Cambridge Analytica had collected and sold personal data of millions of Facebook users without their knowledge or consent”- an incident which is not public knowledge.66

Although it is argued that both laws are significantly similar, the differences make them unique and applicable to a variety of subjects. The GDPR and the CCPA cater to different privacy issues as the GDPR “focuses on protecting human rights and social issues,” while “the U.S. seems to be concerned with providing a way for companies collecting information to use that information while balancing the privacy rights that consumers expect”.67 The reason behind this distinction in their applicability is the difference in the ideologies underpinning data protection laws in the EU and the US.68

I. Comparative Analysis of the CCPA and GDPR

The CCPA is often alleged to be a copy of the GDPR. However, if looked at closely, the CCPA is only similar to the GDPR on a surface level. Overall, it turns out to be fundamentally different from the GDPR.69 The GDPR is a comprehensive piece of legislation extended upon 130 pages and divided into several chapters while the CCPA is a 25- page law covering the major aspects of data privacy in the US.70 The CCPA is built upon the “consumer protection” model and relies on the “notice and choice” premise.71 In contrast, the GDPR is built upon the foundation that data protection is a fundamental right guaranteed by the Constitution and the CFR, just like the right to dignity, free speech, and free trial.72 The GDPR resulted in many companies updating and changing their privacy policies either to go beyond the scope of GDPR or to block their services to EU citizens in order to avoid heavy penalties under the GDPR.73

An opt-in consent does not assume consent, but rather asks users for consent through a notice or form. However, opt-out consent assumes consent and is not actively obtained. The GDPR adopts an opt-in approach which means that data collectors need to ask the users for consent before collecting their data and the definition of consent under the GDPR is one that requires opt-in consent from the subjects prior to any data processing.74 The GDPR has also eliminated any possibility of opt-out consent from its other articles as well.75 Moreover, under the GDPR, the data subjects are allowed to withdraw consent at any time and the companies are under strict requirements by the GDPR to not process the data of subjects beyond the limit for which they have given informed consent. This requirement of the GDPR “changes the paradigm so that companies are under stringent standards to abide by new regulations and rein in ways that companies may have misused personal data for their own profit-generating purposes”76 and the companies choose compliance over heavy fines. However, the CCPA adopts an opt-out approach and requires the customers to opt-out of the businesses if they do not want the selling and processing of their personal data to third parties.77 It also requires businesses to give customers a notice that their data is being sold to third parties and that they have the choice to end this sale of data by opting out. The businesses will not use the personal data of a customer who chose to opt out for about twelve months after receiving the opt-out request. The CCPA also requires corporations and businesses to have an active link to “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” on their websites as well as privacy policies for customers to opt-out.78 The CCPA gives a narrower right to the users to opt-out as compared to the GDPR’s broader right to opt-in with informed consent, because in the former, the personal data of the user is being collected by default unless they actively opt-out.”79 The only time the CCPA mentions opt-in measures is for financial incentives to the customers for selling and processing their data.

The GDPR, under Articles 16 and 17, gives data subjects the right to be forgotten which essentially empowers them to erase or rectify their personal data by putting a request to the controllers. Controllers are under the duty to act upon such requests and also inform the recipients of that data.80 In contrast, the CCPA has a “right to delete” provision and there is no mention of the right to be forgotten. This right to deletion empowers the users to put a request for deleting their personal data and the controllers are obliged to act upon the request and inform the businesses under their privacy policy. However, unlike GDPR’s “right to be forgotten”, CCPA’s “right to delete” is subject to some exceptions like the contract between the user and the controller.81 The GDPR’s right to be forgotten finds its roots in the Google Spain SL case 82 while the CCPA’s right to delete is a narrow scheme of providing some control to the user over their data.

The CCPA and the GDPR both have extra-territorial scope and apply to corporations operating out of the territorial bounds of the EU and the state of California. The scope of the CCPA can be analysed by looking at the definition of “business” which includes entities of any legal form such as sole proprietorship, partnership, company or other separate legal entities which collect personal information of consumers and operate in the State of California, and satisfy “at least one of the thresholds identified in the CCPA.”83 The corporations do not need to be physically present in California or be a Californian corporation or entity to fall under the scope of the CCPA.84 Similarly, the scope of the GDPR can be found in its Article 3 which states that it applies to the data processor or controller in the European Union irrespective of whether the processing is done in the Union or not; the data subjects in the European Union irrespective of whether the processing of their data is done in the Union or outside of it; and the data processors and controls outside of the Union as long as they come under the ambit of the laws of the member states of the Union by virtue of public international law.85 Furthermore, the CCPA applies only to for-profit entities while the GDPR applies to both for-profit as well as non-profit entities.86

Although the CCPA and the GDPR define “personal information” and “personal data” very broadly, the former excludes publicly available information or data from the definition while the latter does not.87 Apart from that, the GDPR creates certain categories of sensitive data and calls them “special categories of data” and sets the bar higher for the protection of such data while CCPA does not have such a taxonomy of data.88 Another important difference between the CCPA and the GDPR is the range of penalties. Under the CCPA, the civil penalty for unintentional breach is 2,500 dollars and for intentional breach, it is 7,500 dollars.89 Under the GDPR, serious breaches can result in fines of up to 20 million euros or 4% of global turnover.90 Google, in 2019, faced the highest amount of fine under the GDPR, amounting to fifty million euros for violating the GDPR rules.91 It was justified by saying that Google deprived its customers of the guarantees provided by Article 6 of the GDPR regarding the “lawfulness of processing.”92

The CCPA has a separate provision for the “Right to Be Free from Discrimination” which prohibits controllers and businesses from discriminating against users if they exercise any of their rights under the CCPA, such as the right to delete their personal information.93 The GDPR does not have a separate provision for non-discrimination, however, it prohibits controllers from discriminating against any user. The GDPR under the “special categories of data” sets a high bar for protection against information that may lead to discrimination and such data includes:

[P]ersonal data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership, and the processing of genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person’s sex life or sexual orientation.94

While the EU remains firm in protecting data against controllers and businesses, the US still faces challenges as the companies try to bypass the CCPA. The CCPA and the GDPR are still leaders in the field of data protection and their influence would impact businesses and service providers to amend their privacy policies as well as their handling of users’ personal data. The biggest impact of the GDPR was the enactment of the CCPA which cannot yet be predicted as it is a “landmark act that is yet untested, covering new grounds in the state of California, and therefore remains a fertile ground for businesses to continue the fight to weaken the CCPA.”95 However, the regulatory rule under the CCPA is expected to shift in 2023 from the Attorney General having authority under the CCPA to the California Privacy Protection Agency under the California Privacy Rights Act (“CPRA”) which would increase the obligations of businesses as well as the protection of consumer’s personal data.96 This would be a milestone for the US in the field of data privacy and the adoption of federal privacy law.97

The Current Data Protection Law in Pakistan

Unlike the US and EU, Pakistan does not have a defined legislation that deals with the aforementioned caveats of tech and data. Nevertheless, other legislations deal with this issue to some extent. The first and foremost issue of Information Asymmetry is the hallmark of the notice and choice model. Since the notice and choice model is simply an online contract, primary contract law may deal with the issue to some extent. In this regard, the Contract Act 1872 (“Contract Act”) must be discussed.

I. The Contract Act 1872

Under the Contract Act, a communication, offer, or notice is deemed to be “complete when it comes to the knowledge of the person to whom it is made.”98 In the digital world, this essentially means that once the platform has shown users the privacy policy, it has completely and entirely fulfilled its duty of communication of offer to the user and it is now up to the user to either accept or reject it. With the proposer’s duty being fulfilled, the next step is to be taken by the acceptor. Section 7 of the Contract Act deals with acceptance. It stipulates that acceptance must be absolute, unqualified, and in a reasonable manner. And if the method of acceptance is stipulated in the proposal, then acceptance must be in that manner.99 The phrases used in these provisions are problematic in the digital world. An acceptance being absolute typically means that the user must accept the proposal right there without having any choice of negotiation. In the digital environment, this practically favours the platforms as they usually present a standardised form. In this situation, the users have no bargaining power. Therefore, when users accept the offer, it is an absolute acceptance. The method of acceptance is the clicking of the “Agree” button at the bottom of a notice. When the user makes the click, the contract is practically complete under the purview of the Contract Act.

If the Contract Act were to govern the notice and choice model as inherited by digital spaces, the issues discussed would persist as both parties would have essentially completed their duty under the Act. Even when both parties have fulfilled their duties, the user is partially, and in most cases, entirely unaware of the terms of the contract.100 The Contract Act is based entirely on the principle of rational consumers. A rational consumer gives their consent when they agree with the other party.101 Whether or not they are aware of what they agreed to is not of much significance as they had the opportunity to make themselves aware and they chose not to avail it. The discussion above makes it clear that consumers do not act rationally on these platforms while signing up. The Contract Act being entirely for rational consumers cannot effectively regulate digital contracts. This can be highlighted from jurisprudence on non-reading of contract.

Non-readers of contract, under Pakistani law, are not granted any protection. The failure of one party to read and understand contractual terms cannot be held against the innocent one, provided that sufficient notice was given to the accepting party. However, pardanashin ladies are afforded special protection under Pakistani law. This is so because such women are deemed to be illiterate and any contract with them must be done carefully as they are incapable of understanding complex written documents. In such cases, it is essential that the party in power explains the contract and its consequences appropriately to the pardanashin ladies before they sign the document. This was highlighted in Siddiqan v. Muhammad Ibrahim,102 where the Court held that a pardanashin lady was not informed about the contract appropriately, therefore, the contract was executed under undue influence. Nevertheless, this is a special protection afforded to pardanashin ladies only. When the acceptor is capable of reading the contract but chooses not to the benefit does not lie in their favour.

Nevertheless, users can raise the defence of being unduly influenced under the Contract Act. However, this plea is also most likely to fail considering other dynamics. Section 16(3) of the Contract Act states that where the balance of power lies in favour of one party, the dominated party enters into a contract with such party, and the transaction appears on the face of it to be unconscionable, then the presumption of undue influence will lie in favour of the party being dominated.103 However, considering that digital contracts are standardised, and the user base is huge, the plea of undue influence will fail as the market is structured in such a manner. Illustration (d) of Section 16 pertains to Subsection (3) and further makes the provision clear that where the market is the key factor for an unconscionable-looking contract, such a contract will not be considered to have been caused by undue influence.104 Therefore, the Contract Act fails to protect individuals from the perils of notice and choice.

Where the Contract Act fails to adequately protect individuals from improper incorporation into platforms, the Consumer Protection law must be evaluated to consider protection to individuals after incorporation onto the platform user database.

II. Consumer Protection Act 2005

In some countries, such as the US, consumer protection law has intentionally been kept so broad as to bring digital platforms under its purview. Recently, the CCPA was enacted which protects individuals from privacy invasions and illegal data usage and practices. However, the Punjab Consumer Protection Act 2005 (Consumer Protection Act) is an ancient law considering new challenges. This Act is applicable only to products supplied by any person or company and not to services on digital platforms.105

Nevertheless, even if the Consumer Protection Act applied to digital platforms, the law is inadequate for providing protection to users. The primary reason is that just like the Contract Act, this law is premised on the principles of rational consumerism. The Consumer Protection Act imposes a duty on suppliers to disclose information to consumers. In the general sense, the notice in the form of the privacy policy shall serve this purpose and should be enough to fulfil the obligation under this section. Furthermore, digital platforms also tend to manipulate user choices through advertisements and other means.

Section 21 of the Consumer Protection Act protects individuals from such manipulation, nevertheless, corporations can identify consumer biases and cognitive lacunas to practically target their vulnerabilities in favour of the platform.106 Even so, the section does not adequately protect individuals as a rational consumer is required to read the terms of the privacy policy, which essentially enumerate all of these “services.” The privacy policy acts as a liability waiver for the platforms while the user is afforded no protection under consumer protection law. Thereby, the consumer protection law in Pakistan does not adequately protect individuals during and after incorporation into the platform. However, it is essential to discuss the protection and remedies available to users of these platforms from data system breaches and their illegal usage to completely assess the efficacy of the current system.

III. Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016

The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016 (“PECA”) is critical for this discussion. Sections 3-8 and 20 of PECA primarily deal with the issues of criminal data breaches and forging. Where these sections elaborately cover individuals who engage in such data breaches, the PECA does not talk about platform accountability. The cases that have been registered under these sections of the PECA pertain to private individuals who breached data, as hoarded by platforms, and used them illegally. In Junaid Arshad v. The State, a person was tried for acquiring images of a woman from social media and forging them to make them graphical.107 The case did not talk about platform accountability even though the accused was using a fake account to acquire images of the victim.

In Muhammad Usman v. The State,108 the accused was tried for leaking nude photographs of a lady which were acquired and transmitted through WhatsApp. While the Court successfully incriminated the accused for his acts, WhatsApp was not involved in the process. Nevertheless, the law is somewhat effective in penalising individuals who engage in data-breaching activities.

Moreover, PECA provides a provision for illegal usage of identifying information under Section 14. This provision offers protection to identifying information of any person, but it is all subject to approval. If approval is gained through an agreement, then the person cannot be held accountable. The platforms are thereby protected under their privacy policy because it is accepted by their users. So, this provision makes way for privacy policies to act as liability disclaimers for the companies. Consequently, all cases brought under this section are against individuals and not against platforms. In Muhammad Nawaz v. The State,109 the accused was prosecuted for forgery and unauthorised usage of a car’s invoice. Platform liability and duties in this case were not discussed either.

In addition to the aforementioned reasons for not taking any action against corporations, Section 35 of the PECA limits the liability of service providers in cases where the platform simply failed to act. The PECA does not place any liability on platforms for not adequately protecting its users’ data, which is primarily the reason for not registering any case against a platform under this Act even though other countries prosecuted companies for the same breaches. In 2018, Careem, a ride-hailing company, revealed that the data of its users had been compromised. Nevertheless, Pakistani authorities were unable to hold the company accountable regarding the data breach of Pakistani users despite Careem having its offices in Pakistan.110 Similarly, when 50 million Facebook accounts were compromised, Pakistan did not have adequate laws to cater to the issue. In contrast, the European Union acted against Facebook and imposed fines under the GDPR.111 The positive aspect of the PECA is that the authorities work with the platforms to bring about justice for the victims as seen in Kashis Dars v. The State.112 Nevertheless, as a failure of the law, it must be noted that no method of platform accountability has been ensured under the PECA.

The current data protection regime in Pakistan is not effective at protecting its users against the perils of big data and big tech. They fail to protect individuals against inadequate consent, profiling, dark pattern manipulation, and data breaches. Therefore, there is a need for data protection laws in Pakistan, such as those enacted in countries around the world. Owing to this need, the Ministry of Information Technology & Telecommunications has been working on drafting Data Privacy legislation since 2018. The fourth draft of the bill was published in the latter half of 2021. The next section of this paper will discuss the efficacy of the Personal Data Protection Bill 2021 (“Bill”) along with suggestions and recommended amendments.

Personal Data Protection Bill 2023

The pivotal section of the Bill is the one containing definitions. Section 2(f) defines consent as “any freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s intention by which the data subject by a statement or by clear affirmative action, collecting, obtaining and processing of personal data”.113 On the face of it, the definition seems very elaborate. However, there are several lacunas involved in this. First, the Bill does not define what the term “free” means. This can cause several issues as discussed in Section II of this paper. Because it is difficult to ascertain whether consent means “informed consent” if it is obtained by acceptance of terms that appear before a person through a click or “informed consent” is the one that requires the person to read the terms before accepting. If so, there is no way to be sure that users have read the terms and are entering into an agreement after making an informed decision. Therefore, the Bill needs to particularly establish what free and informed consent means and how it is to be obtained through the procedure stipulated in subsequent sections. The second issue with regard to definitions concerns the applicability of the law.

Under Sections 2(a) and 2(ee), the Bill provides the definition for anonymised data and pseudonymisation respectively. It also needs to be highlighted here that under Section 2(z) personal data has been defined, which has been afforded due protection through this Bill. Nevertheless, Section 2(z) stipulates, “anonymised, or pseudonymised data which is incapable of identifying an individual is not personal data.”114 Essentially, this Bill does not cover or protect anonymised or pseudonymised data. This is particularly worrisome as it has been discussed in Section II of this paper that anonymised data is not really anonymised and can be used to retrace the origin or source of the data.115 Anonymised or pseudonymised data is identifiable and hence requires to be treated as personal data. The drafters should focus on broadening the scope of the Bill to include all information that is directly or indirectly identifiable to ensure maximum protection for individuals.

Sections 5 and 6 of the Bill retract back to the issue of consent. Section 5 of the Bill does not explicitly state that special consent is required for the collection of data. This can be problematic in cases of collection of data such as the internet activity of a person. Section II of this paper discusses that such data can be identifiable, therefore, adequate protection must be afforded to it. Furthermore, Section 6 states that data controllers must obtain the consent of users or data subjects before they can process the data, similar to the opt-in approach adopted by the GDPR. However, unlike Article 32 of the GDPR which stipulates the method of obtaining consent through different means, no method of acquiring consent has been mentioned in the Bill. This essentially makes the law inadequate as companies can be entirely compliant with the law by practically working the way they currently do. Therefore, the Bill must explicitly state the method of consent. It is recommended that a special obligation must be imposed on data controllers to design the consent form or the notice in such a way that it includes less text and more digital representation of the harms and benefits associated with collection and processing. This is known as the visceral notices approach for consent and has been held effective for obtaining informed consent through research.116

Similarly, Section 7 of the Bill requires the data controllers to send notices to the data subjects informing them about the processing and collection of their data. This is similar to the CCPA’s requirement of giving notice to the user before their data is being processed. It is encouraging that the section covers the bases very broadly, however, it is concerning that the primary issue of consent and inadequate notices is not being resolved. Including more text into notices and consent forms is destined to fail for the reasons of the complexity of language, the inability of the users to read and understand the lengthy and ambiguous notices, non-reading by the users, and cognitive bias of the reader – as discussed in Section II. Therefore, special consent should be obtained through visuals, text, and affirmative actions, such as multiple pages of terms and conditions with an “accept” button instead of one display page. Furthermore, the provisions shall explicitly state that all data subjects must be given notice and asked for consent as default on any given platform while joining the platform. Cognitive biases of people cause them to accept terms without reading them and generally stick to default options. Therefore, it must be ensured that each website takes consent for the bare minimum data required for the platform to function for the user from the initial consent form. Furthermore, for any future services or enhancing layer on data procurement and processing a special consent shall be obtained.117

In addition to the issues on consent, Section 7 does not impose an obligation to obtain consent and give notice to the users about their profiling from tracking on and across platforms, automated decision making, and whether the data controller intends or has provisions for transferring data to third countries. Furthermore, the section fails to put any sanctions in case the data controllers fail to comply with the provisions on consent and notices. The issue of tracking and profiling needs to be dealt with very strictly under this Bill, which has been largely excluded. Profiling and its subsequent usage for advertising, predictive analysis, and other processes has immense issues such as manipulation and dark patterns. In this regard, retention and usage of data is also very important.

Section 10 of the Bill is significant as it imposes restrictions on the retention of data and puts an obligation on the controllers to delete the data when it is no longer required for the purpose for which it was collected. This section is similar to the “right to delete” given in the CCPA but is also distinguishable from that right in the sense that it puts an obligation on the controllers to delete data. However, under the CCPA, the users are under an obligation to request the deletion of their data when it is no longer required. It must be noted here that the conditions stipulated are considerably weak. Platforms like Google essentially keep data to continue building on it and to keep using previous and new data together. It is recommended that data erasure shall be made mandatory on a yearly basis. Only the very basic information of each user shall be retained. Furthermore, every data subject shall have the right to unconditional data erasure. The concept of the “right to be forgotten” as conceived in the GDPR should be included within the Bill as it gives the users more control over their data and empowers them to not just erase their data but also rectify it. Section 26 of the Bill is more similar to the CCPA’s “right to delete” as it grants the data subjects the right to erasure of their personal data. It is problematic for being conditional and for not providing complete deletion of all information of the data subject whether identifiable or not. Furthermore, the provision for erasure within fourteen days is too relaxed considering that personally identifiable information is at stake. Nevertheless, the provision for erasure under Section 26 and data correction under Section 11 is appreciated. However, there is a need for both provisions to be broadened to ensure better protection of users’ data. Most of the provisions of the Bill deal with the collection and processing of information. However, another issue associated with data hoarding is that of data breaches.

Section 13 of the Bill imposes a duty on data controllers to disclose to users and the commission when data is breached. The lacuna under this section is that where the controller believes that the breach is not likely to cause harm to the rights and freedom of subjects, they are not obligated to notify users of the breach. Furthermore, the provision does not talk about the platforms’ accountability in cases of breach. GDPR of the EU provides provisions for actions against platforms in case of breach. Due to this provision, the Information Commission Office was able to fine British Airways €20 million for the breach affecting more than 400,000 customers.118 Therefore, it is essential that provisions for such sanctions and fines are put in place within the law while it is still at the initial stage.

Chapter VI of the Bill talks about cross-border data transfers. These sections are like the GDPR as they also require the recipient countries of data to have data protection at least equivalent to the extent to which this Bill provides. Where the sections provide adequate safeguards regarding the level of protection afforded, it is unclear as to which Pakistani authority is to ascertain the adequacy of the foreign country’s data privacy laws. Article 45 of the GDPR lays down all the elements which need to be examined by the Commission to assess the adequacy of the level of protection provided by third countries.119 Under the GDPR, the Commission is required to maintain a list of countries that have adequate privacy protection laws for such transfers. It is suggested that the Commission shall be given the power and duty to maintain such a list. Furthermore, it must be mandatory for controllers to obtain permission before such transfers.120

The next important provision is Section 24 of the Bill which talks about disclosure other than the purposes for which the data subject consented. This section sets out certain conditions under which personal data can be collected and processed without the data subject’s consent. This section is problematic as it assumes consent from users. Subsections (c) and (d) allow data controllers to disclose data where they have a “reasonable belief” that it is legal for them to do so, or that they would have had consent if they asked the subject for it. The provision is too broad and the standard of “reasonable belief” is too low. Therefore, it needs to be amended to something more rigid. Furthermore, the assumption of consent should be allowed in limited circumstances, and the Bill should spell them out explicitly rather than allowing the controller to decide.

Overall, the law covers some bases regarding consent, which need to be made more stringent. Moreover, special provisions are necessary with regard to data disclosure, transmission, deletion, and the right to be forgotten. Profiling users’ needs to be regulated to protect the autonomy and privacy of individuals. Conclusively, the Bill is a step in the right direction, nevertheless, it still requires major changes to come to an equal standing with its counterparts.

Conclusion

The right to privacy in Pakistan emanates from the Constitution as well as Islamic principles which forbid invading the privacy of others. It considered a fundamental right in Pakistan and has been interpreted in a way to include digital privacy. Unlike other countries, Pakistan does not have an exhaustive data protection law. The existence of such a law has become crucial due to the tangible harms attached with big data and big tech, such as information asymmetry; inadequate consent mechanisms; opacity of data collection and its processing; user profiling and the exploitation associated with it; mass use of platforms as tools for control and surveillance; platform’s use in illegal involvements such as elections; illegal or uninformed sale and transfers of data; and other issues such as data breaches and wilful leakage of databases. Pakistan’s current regulatory framework like the Contract Act 1872, Consumer Protection Act 2005, and the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016 are not adequate enough to deal with issues pertaining to digital privacy. The drafting of Pakistan’s Personal Data Protection Bill 2021 is a step in the right direction. The fact that this is the fourth amended version of the Bill shows the ministry’s interest and seriousness towards solving the issue of data protection in Pakistan. The Bill possesses substantial similarities to the CCPA and the GDPR but fails to adopt their practical aspects. Although the Bill tries to hold the data controllers accountable and give the users control over their personal data, it has practical lacunas that need to be amended.

_______________________________________________________

* Muhammad Hammad Amin is a lawyer based in Lahore, Pakistan, specializing in corporate and constitutional law. He graduated with B.A.-LL.B. (Honours) from the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in 2022. He currently serves as a valuable member of RMA & Co, where he consistently handles prominent constitutional and political cases while providing expert counsel in corporate affairs.

Maira Hassan is a B.A.-LL. B (Honours) graduate from LUMS. She is currently working as a Judicial Law Clerk at the Supreme Court of Pakistan and serving as an Environmental Law Advisor for the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Cities Improvement Project funded by the Asian Development Bank.

1. The Constitution of Pakistan 1973, Article 14.

2. PLD 1998 Supreme Court 388.

3. Ibid [29].

4. 389 U.S. 347.

5. Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto (n 2) [29].

6. Ibid [33].

7. The Constitution of Pakistan 1973, Article 9.

8. Kh. Ahmed Tariq Rahim, v. Federation of Pakistan PLD 1992 SC 646.

9. Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto (n 2) [25].

10. The Constitution (n 7) Article 227(1).

11. PLD 1998 Lah 35.

12. The Code of Criminal Procedure 1898, ss 96, 98, 165.

13. 2007 YLR 1269.

14. 2009 PCrLJ 744, [7].

15. Ibid; see also Muhammad Abbas v. The State 2005 YLR 3193.

16. PLD 2010 Quetta 21, [6].

17. Chamber of Commerce and Industry Quetta Balochistan through Deputy Secretary v. Director General Quetta Development Authority PLD 2012 Bal 31, [9].

18. Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: Public Affairs 2019), Ch 3.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Jordan M. Blanke, ‘Protection for ‘Inferences Drawn’: A Comparison Between the General Data Protection Regulation and the California Consumer Privacy Act’ (2020) I(2) Global Privacy Law Review 81–92, 82.

22. Ibid.

23. Andrew Bloomenthal, ‘Asymmetric Information’ (INVESTOPEDIA, 7 Apr 2020) <https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/asymmetricinformation.asp> accessed 4 Nov 2020.

24. Robert H. Sloan & Richard Warner, ‘Beyond Notice and Choice: Privacy, Norms, and Consent’ (2014) 14 J High Tech L 370, 373.

25. Ibid 374.

26. Kritika Bhardwaj, ‘Preserving Consent within Data Protection in the Age of Big Data’ (2018) 5 Nat'l LU Delhi Stud LJ 100, 101.

27. Ibid.

28. Sloan & Warner (n 24) 374.

29. Ibid; See also Susan E Gindin, ‘Nobody Reads Your Privacy Policy or Online Contract? Lessons Learned and Questions Raised by the FTC's Action Against Sears’ (2009) 8 Northwestern Journal Technology &Intellectual Property 1; Shara Monteleone, ‘Addressing the ‘Failure’ of Informed Consent’ (2015) 43 Syracuse J. Int’l L. & Com. 69, 79.

30. Ibid; Sloan & Warner (n 24) 380.

31. Omer Tene and Jules Polonetsky, ‘Big Data for All: Privacy and User Control in the Age of Analytics’ (2013) 11(5) Nw J Tech & Intell Prop 239, 261.

32. Sloan & Warner (n 24) 380; See also One Stop Supply, Inc. v. Ransdell 1996 WL 187576.

33. Margaret Jane Radin ‘Humans, Computers, and Binding Commitment’ (2000) 75 Indiana Law Journal, Article 1125.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Sofia Grafanaki, ‘Autonomy Challenges in the Age of Big Data’ (2017) 27 Fordham Intell Prop Media & Ent LJ 803, 831.

37. Arvind Narayanan & Vitaly Shmatikov, ‘Robust De-anonymization of Large Sparse Datasets’ (2008) IEEE Symposium on Security & Privacy 111, 119.

38. Tene and Polonetsky (n 31) 251.

39. Chris Soghoian, ‘Debunking Google's log anonymization propaganda’ CNET NEWS (11 Sep 2008) <https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/debunking-googles-log-a…; accessed 1 Dec 2021.

40. Tene and Polonetsky (n 31) 252.

41. Kashmir Hill, “Resisting the Algorithms” (2011) Forbes <https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2011/05/05/resisting-the-algor…; accessed 2 Dec 2021.

42. Paul Lewis and Paul Hilder, “Leaked: Cambridge Analytica's blueprint for Trump victory” (2018) The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/mar/23/leaked-cambridge-analyt…; accessed 3 Dec 2021; see also Nicholas Confessore, “Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far” (2018) The New York Times <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scan…; accessed 3 Dec 2021.

43. Ibid.

44. Tene and Polonetsky (n 31) 252.

45. Ibid.

46. Ibid.

47. Grafanaki (n 36) 831.

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid 832.

50. Ibid 833.

51. Rys Farthing and Dhakshayini Sooriyakumaran, ‘Why the Era of Big Tech Self-Regulation Must End’ (2021) 92(4) Australian Institute of Policy and Science 3–10.

52. Anupam Chander, Margot E. Kaminski, and William McGeveran, ‘Catalyzing Privacy Law’ (2021) 105 MINN. L. REV. 1733, 1747.

53. Directive 95/46/EC of the European Union.

54. Kimberly A. Houser & W. Gregory Voss, ‘GDPR: The End of Google and Facebook or a New Paradigm in Data Privacy’ (2018) 25 Rich JL & Tech 1, 12.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid 16.

57. Ibid 17.

58. Sahara Williams, 'CCPA Tipping the Scales: Balancing Individual Privacy with Corporate Innovation for a Comprehensive Federal Data Protection Law' (2020) 53 Ind L Rev 217, 221.

59. Directive (n 53) art 25(1).

60. Houser & Voss (n 54) 15.

61. Maximillian Schrems v. Data Protection Commissioner (C-362/14, EU:C:2015:650).

62. Ibid.

63. Grace Park, 'The Changing Wind of Data Privacy Law: A Comparative Study of the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation and the 2018 California Consumer Privacy Act' (2020) 10 UC Irvine L Rev 1455, 1466.

64. Ibid.

65. Blanke (n 21).

66. Park (n 63) 1457.

67. Houser & Voss (n 54) 22.

68. Ibid 9.

69. Chander, Kaminski & McGeveran (n 52) 1746.

70. Ibid.

71. Ibid 1747.

72. Ibid.

73. Park (n 63) 1468.

74. Ibid 1476.

75. Ibid.

76. Ibid 1477.

77. Ibid.

78. Ibid 1478.

79. Ibid.

80. Park (n 63) 1483.

81. Ibid.

82. Google Spain SL v. Agencia Espafiola de Protecci6n de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja Gonzales, 2014 E.C.R 317.

83. W. Gregory Voss, ‘The CCPA and The GDPR are not the Same: Why You Should Understand Both’ (2021) CPI ANTITRUST CHRONICLE 1, 3.

84. Ibid.

85. The General Data Protection Regulation, art. 3.

86. Voss (n 83) 4.

87. Ibid.

88. Ibid.

89. Erin Illman & Paul Temple, ‘California Consumer Privacy Act: What Companies Need to Know’ (2019-2020) 75 The Business Lawyer 1637, 1645.

90. Houser & Voss (n 54) 105.

91. Olivia Tambou, 'Lessons from the First Post-GDPR Fines of the CNIL against Google LLC' (2019) 5 Eur Data Prot L Rev 80.

92. Ibid 82.

93. Illman & Temple (n 89) 1643.

94. Voss (n 83) 5.

95. Park (n 63) 1489.

96. Voss (n 83) 5–6.

97. Ibid.

98. The Contract Act 1872, s 4.

99. Ibid s 7.

100. Lior Strahilevitz and others, ‘Report on Privacy and Data Protection’ (George J. Stigler Centre for the Study of the Economy and the State, 2019) < https://www.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/data--- report.pdf> accessed 4 Nov 2020, 12–13.

101. The Contract Act 1872, s 13.

102. 1993 MLD 1979.

103. The Contract Act 1872, s 16(3).

104. The Contract Act 1872, s 16(3) & Illustration (d).

105. The Punjab Consumer Protection Act 2005, s 2(j); see also, The Sales of Goods Act 1930, s 2(7).

106. Strahilevitz (n 100) 34–36.

107. 2018 PCr.LJ 739.

108. 2020 PCr.LJ 705.

109. 2021 YLR 328.

110. ‘Careem Admits to Mass Data Leak’ The Express Tribune (23 April 2018) <https://tribune.com.pk/story/1693146/careem-admits-mass-data-leak> accessed 3 Dec 2021.

111. Rosie Perper, ‘Facebook could be fined up to $1.63 billion for a massive breach that may have violated EU privacy laws’ Business Insider (1 Oct 2018) <https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-eu-fine-163-billion- massive-data-breach-50-million-users-2018-10> accessed 3 Dec 2021.

112. Kashis Dars v. The State and Two Others 2020 PCr.LJ 259.

113. The Personal Data Protection Bill 2023, s 2(f).

114. Ibid s 2(k).

115. Arvind Narayanan & Vitaly Shmatikov (n 37).

116. Shara Monteleone, ‘Addressing the ‘Failure’ of Informed Consent’ (2015) 43 Syracuse J. Int’l L. & Com. 69, 110; See also, Ryan Calo, ‘Against Notice Scepticism in Privacy (an Elsewhere),’ (2012) 87 Notre Rev. 1027, 1033.

117. Ibid.

118. Information Commission Office, ‘ICO fines British Airways £20m for data breach affecting more than 400,000 customers’ Information Commission Office (16 Oct 2020) <https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/news-and-events/news-and-blogs/2020/10…;.

119. The General Data Protection Regulation, art 45.

120. Ibid.